Agile management originated from software development, where it has been applied successfully for many years. Today it is used in many other areas, such as marketing and customer support. In the following, we illustrate the extent to which universities can benefit from an agile approach.

Agile – What is it?

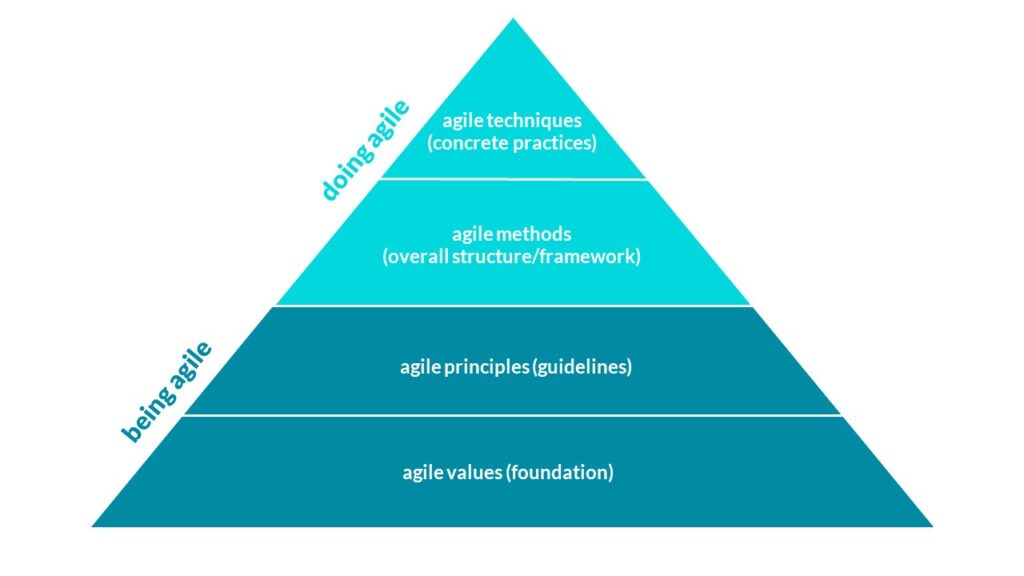

Agile project management originally came from the field of software development. It was developed as an alternative to classical approaches, which many found to be bureaucratic and not very customer orientated. The basis for this is considered to be the agile Manifest, which was published by 17 experts in the field of software development in 2001. It contains four values, which define a certain culture. One of these values is that individuals and interactions take priority over processes and tools. The Manifesto’s signatories derive 12 principles from these basic values which have served as a guideline for a modern form of software development since then (see Figure 1).

These considerations very quickly met with approval. Today they are applied in many other areas, particularly in complex projects or projects where the result cannot be precisely defined from the start (State of Agile, 2023), because if you consider agile principles, you can succeed in reacting to changes flexibly and improving collaboration. If we take a closer look at a selection of agile principles (Preußig, 2020), this becomes very clear:

- direct communication: Direct conversation (e.g. brief team meetings that take place regularly) is preferred to indirect communication (e.g. via documents), as it makes the exchange (of information) faster and easier.

- self-organising teams: In teams that organise themselves, more individual responsibility falls to the members. In the best case scenario, the responsibility is spread equally among all the members of the team and the form of collaboration that prevails is one based on trust. That can lead to greater (intrinsic) motivation. The teams have the expectation that they will continue to grow and improve together.

- close collaboration between the experts in the field: Forming interdisciplinary teams in which different forms of expertise are represented – ideally, all forms that are necessary in order to achieve the goal – can deliver huge synergy effects: the team members help each other acquire any additional competencies that are necessary.

- iterations in short timeframes: A project or process is divided up into small steps. These steps are repeated as often as necessary for the desired result to be achieved. The shorter timescales together with regular feedback (including from the customers) enable the team to make readjustments and adapt to changes quickly.

- simple solutions: To avoid tasks and steps in the process that are not very useful or not useful at all, or where the cost-benefit ratio is not right, the principle of simple solutions is consistently pursued.

To be able to put these agile principles into practice, you need corresponding agile techniques. The most well-known of these include the task board (see below) and Planning Poker, for example. Most techniques can be applied with a well-equipped presentation case.

Meanwhile, there are also various digital tools you can use.In principle, agile techniques can be applied as separate activities in themselves. Many of them complement or build on each other. As a support, there are predefined, framing structures for agile work processes which integrate the individual techniques into an overall concept. These are called “agile methods”, the most well-known of which include Scrum, Kanban and Design Thinking.

Agile in higher education

Views differ as to the extent to which universities support or rather hinder agile developments due to their formal structure and organisation (Mayrberger, 2021). Overall, it can be established that interest has clearly been growing at the different levels of the university as an organisation for some years, including programme development, administration and third-space management. To date, however, agile projects and approaches have only been found at the microlevel of teaching organisation (“agile teaching”, Mayrberger, 2021).

What is undisputed is that agile working methods offer numerous advantages and opportunities, not only in business but also in higher education. Their potential should therefore be used more widely at all levels.

Agile approaches can improve the collaboration and exchange within the (teaching) team, with other facilities in and outside the university and also with the students. One of the ways that this can work is by having regular team meetings and short feedback loops. Both the overall planning and the prioritisation of upcoming activities is done together as a team. Tasks, responsibilities, processes and progress are visualised for everyone concerned, with the options of an analogue or digital visualisation.

Lecturers and students benefit equally from the advantages of agile teaching. Students are actively incorporated into the design of the lecture or seminar by being involved in establishing the educational paths and focus of the content, for example. The entire learning process is subsequently divided up into manageable steps and visualised appropriately. In combination with regular feedback loops and reflections, this structure helps the students organise their learning process themselves. The role of the lecturer changes in that they are no longer responsible for imparting knowledge but are primarily responsible for supporting the students in their process. An additional bonus for the students lies in their becoming acquainted with and applying principles and working methods that they will increasingly come across in future jobs (Arcaro & Gähl, 2020).

In the context of programme and curriculum development, students should be included early on in their role as “customers”. Their needs, wishes and feedback are valuable information. That way, misunderstandings can be recognised and cleared up early.

Two practical examples from university

With regard to agile working, university staff can just apply selected techniques or they can work according to an agile method (e.g. Scrum). For you to get a better idea of what agile management can look like in practice at university, we have presented each option below based on a concrete example.

Organisation of the round table “Innovation in university teaching” with the help of a task board

The organisation of the round table on the subject “Innovation in university teaching” serves as the first practical example. This was held by the ZHW at the University of Regensburg. There were many different things to do for the round table, such as organising an introductory presentation, finding debaters, looking for a room, advertising, website and catering, etc. This involved different people and departments, like the central library, the student union and the ZHW.

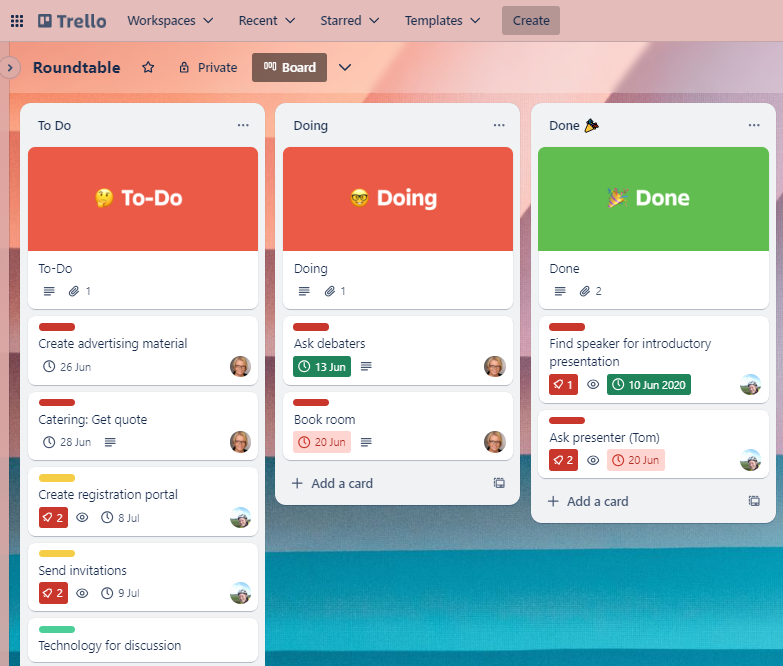

At the start it was important to compile a list of tasks and to set priorities, with, the individual tasks being sorted according to priority – high, medium and low – and accordingly selected as the next task to do (see Figure 2 for task examples).

In a project involving a large number of tasks, there is the fundamental danger of your losing track. To prevent this and enable good coordination, you can use a task board. That way, you can easily visualise what things there are still to do, which have already been started and which have been done. The task board can be used both in analogue and digital form. The organisers of the round table were often not at the same location, which is why Trello was used as a digital solution in this case. This tool is very suitable because you can not only set different columns with To Do, Doing and Done, but it is also possible to set a date and store documents that all board members can access. For each task, a card can be generated that can be moved accordingly from left to right. In addition, responsibilities can be defined on each card.

eduScrum in Maths lectures

Another option for agile working in higher education is to use eduScrum. This method is successfully applied at the University of Mannheim. eduScrum is used in Maths lectures for mechanical engineering students as an active lecture form. That means that the students work on tasks independently as teams within a set period. The difference from conventional project work is that the learners plan and structure their working steps themselves. The lecturer’s task is to set learning outcomes, be available to the team as a coach and to help with any questions. The students receive a booklet containing the learning outcomes in which the formulae and calculation methods are highlighted in colour. Tasks and literature references are given for each topic.

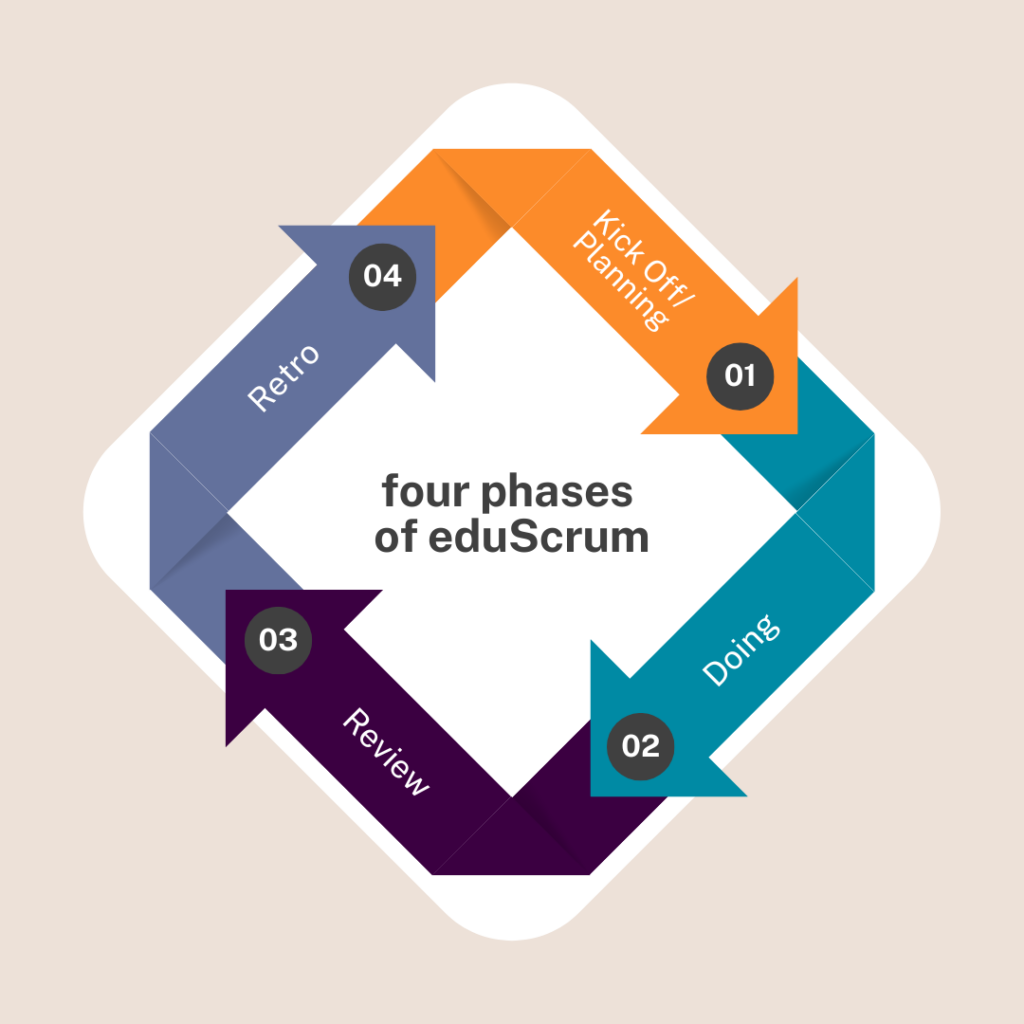

The procedure during the Maths lectures is divided into four phases.

Phase 1: Kick-off/Planning phase (20-30 minutes)

At the kick-off, an overview is given of the topics to be worked on in the Maths lectures. A teaser is used here to draw attention to the topic. What is important is to create a connection to the subject. The relevance of the subject is also illustrated. The students then have to plan the concrete steps for the coming work phase in their group. The students also receive the booklet.

Phase 2: Doing (1-3 weeks)

In this phase, the students work on the subject matter in their group. Here, both a knowledge repository is set up and the tasks are calculated and discussed in the group. The groups can get individual help from the lecturer if there are any hurdles.

Phase 3: Review (60 minutes)

The review concerns whether the students have understood the subject matter or not, that is, whether the subject matter can be applied – whether the students can pass an exam with the skills they have learned (test of knowledge as well as tasks and situations similar to those that might come up in an exam), for example.

Phase 4: Retrospective (15 minutes)

In the final phase, the collaboration should be reflected on. Here, the team members can discuss what worked well during the collaboration and what working methods could be improved for the next work phase.

The advantage of working with eduScrum is that the students actively work through the subject matter themselves and do not just hear what is said passively. Furthermore, while they are working (instead of lectures) they have the option of contacting the lecturer if there are any hurdles, hence, personalised topics can be explained.

By the way: as with almost all the other posts on lehrblick.de, this blog post was also created with the help of agile techniques (including task board and retrospective) and tools (including Trello and Teams) based on agile principles (self-organising team, iteration, direct communication).

References

Arcaro, I. & Gähl, A. (2020). Mindset für Agile Lehre. DUZ Magazin, 7, 56–59.

Mayrberger, K. (2024). Agile Educational Leadership. https://agile-educational-leadership.de/

State of Agile (2023). The 17th State of Agile Report. https://info.digital.ai/rs/981-LQX-968/images/RE-SA-17th-Annual-State-Of-Agile-Report.pdf?version=0

Preußig, J. (2020). Agiles Projektmanagement: Agilität und Scrum im klassischen Projektumfeld. Haufe.

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Bachmaier, R. & Puppe, L. (2024, July 18). Agile – Inspired by the software industry, adapted for higher education. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20240718.EN

Regine Bachmaier

Dr. Regine Bachmaier is a research associate at the Centre for University and Academic Teaching (ZHW) at the University of Regensburg. She supports teachers in the field of “digital teaching”, among other things, through workshops and individual counseling. In addition, she tries to keep up to date with the latest developments in the field of “digital teaching” and pass them on.

Dr. Linda Puppe

Dr. Linda Puppe is a research assistant at the Centre for University and Academic Teaching (ZHW) at the University of Regensburg. She focuses on the topics of innovation in teaching and motivation. Furthermore, she is interested in digital learning environments.