Accessible or semi-accessible teaching is a very important topic for colleges and universities. But what does accessible or semi-accessible teaching mean? And how can it be implemented? Below, we would like to answer these two questions and, among other things, offer you three simple tips to help make your teaching more accessible.

Accessible or semi-accessible teaching in higher education means that instructors prepare their classes so that persons with disabilities do not experience any disadvantages when participating. Semi-accessible therefore means concretely that the use of teaching material is optimized e.g. with screenreader software or that the examination format is adapted for people with motor limitations (alternative oral exam instead of written exam). Organizational measures, such as the selection of a wheelchair-accessible room or the provision of a sign language interpreter, also fall under this broad heading.

In reality, the accommodation of students with disabilities in higher education is usually more difficult to implement than it is in theory. Particularly in digital teaching, barriers can arise through the use of text, audio or video material. Some instructors can be discouraged by the extra effort, while others are simply unaware of certain barriers.

From the diverse portfolio of options for designing accessible instruction, we have selected the following three, easily implementable and highly effective tips.

Provide organizational information in good time

Many barriers can be avoided in advance if you provide organizational information in good time. Clarify details, such as the location, the requirements demanded of participants, criteria for passing, options for communication, etc., already at the time of registration for the course. Details regarding the location, e.g. wheelchair accessibility, can be just as relevant as the type of output required or the offering of appropriate alternatives.

- Course dates and times: For students with disabilities, it is often more difficult to get to the course location, so more time must be planned for.

- Course location: The early announcement of the course locations makes it possible for your participants to research accessible points of access or technologies on site (e.g. work stations for students with visual impairments).

- Prerequisites for participation: If e.g. a reader is given as a prerequisite, a student with visual impairment must search for a compatible, digital alternative.

- Teaching/learning material: Try to provide the learning material as early as possible. This makes it easier for your students with disabilities to process it.

- Required “materials”/hardware: Provide information in advance about materials or hardware required for participation. That way, students can check whether they already have the right device or whether they have to adapt it.

- Deadlines: Publish deadlines for registration, assignments, presentations, exams, … in good time. For persons with disabilities, planning a semester is more difficult. It is therefore advantageous for them to be able to know and plan for intermediate goals. Only use time limits in exceptional cases. If you work with deadlines, set them generously and allow for justified extensions.

- Compensation for disadvantages: Often, students are unaware of all the options for compensating for disadvantages or they do not take advantage of these. In addition, those affected often do not always communicate their disabilities voluntarily. Therefore you should be transparent in your communication and explicitly inform your participants of this. Signal that you would like to communicate openly about this issue.

In summary: Any information and material you provide in advance helps those affected, including to dispel their misgivings.

On the website Students with Disabilities, the University of Regensburg lists various offerings for students: from information on compensating for disadvantages to mentoring offerings. Inform yourself in advance about possible assistance offers and also inform your participants about the options available.

Plan your teaching method in advance

Reducing psychological barriers afterwards is usually more difficult than planning for them in the first place. So keep the issue of accessibility in mind in the planning phase of your course:

- In terms of accessibility, the division of your course into synchronous and asynchronous sections plays a central role. Synchronous sections (in-person meetings or Zoom meetings) represent a greater burden for persons with disabilities. Asynchronous elements (e.g. asynchronous learning videos, self-learning modules, etc.) make it possible for participants to organize their time individually, thereby allowing for an individual learning pace. The opportunity to include breaks, to learn independently or to pause or rewind videos as necessary makes it easier to cope with instructional material.

- Time-limited question/answer formats can be problematic because they demand a certain “learning pace”. Students with hearing impairments are therefore disadvantaged in oral variants, while students with visual impairments struggle with written question/answer formats.

- Collaborative methods which include a high degree of communication and discussion should definitely be allotted generous amounts of time.

Designing accessible materials

Adapted instructional materials are a very practical place to start. The effort involved in removing barriers is not always minor, but can significantly increase the quality of the teaching material. Below, we will concentrate on the most commonly used software, Microsoft PowerPoint or Word and Adobe PDF. Many of the tips, however, can be applied to their alternatives as well.

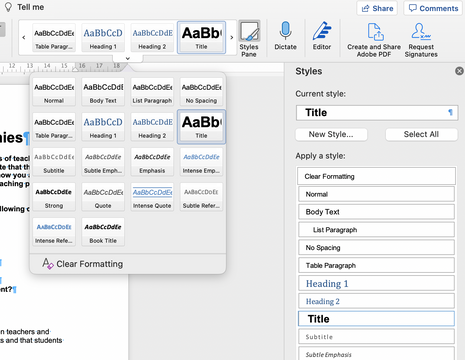

The primary barrier in the creation of documents is the lack of preparation of the contents for screenreaders. In order to efficiently “navigate” a document with a screenreader, students with visual impairments must have a clean document structure.

This is primarily solved by means of a simple method, i.e. the use of formatting templates.

The titling of content as “what it essentially is” makes it possible for users of screenreaders to easily navigate through the document and grasp its structure.

Not all formatting templates are equally relevant. The most important elements are:

- Paragraphs

- Headings

- Lists

- Links

- Tables

- Images and graphics

If the design of an element does not fit into the overall picture, it is always a good idea to adjust the formatting template instead of editing the individual element. With a right click on an image or graphic, the option “Edit alternative text” can be selected and a description of the graphic can be entered. In this way, you can describe the graphic for participants with visual impairments and make it “visible”.

If you apply this procedure consistently for an entire document, screenreaders will be able to recognise and identify each formatting element. When correctly exported into another document format, e.g. a PDF document, the structure is retained and so no further adjustments are necessary.

Analogously to the use of formatting templates in word processing programs, it is a good idea to use slide templates for presentations. The slide design and structure (e.g. background color, font size, etc.) is thereby determined through the use of a so-called master slide.

The TU Dresden has provided comprehensive explanations on the procedures for Microsoft Word, Microsoft PowerPoint and Adobe Indesign.

Conclusion

Accessibility is a broad and complex field. With our tips and a manageable amount of effort, you can achieve a clear improvement in the area of accessibility. We do not wish to whitewash the fact that many barriers remain, such as the subsequent subtitling of videos or the reworking of existing PDFs. Clearing these away requires significantly more time and advanced expertise in this area.

It is extremely important to signal to persons with disabilities that you are aware of their problems and are ready to solve them. Openness for discussion and forward-looking communication are the key to success. By communicating to your participants that they can come to you with their problems, you have already removed the greatest barrier to accessible teaching.

Suggestion for citation of this blog post: Greiner, F. (2022, March 24). Three Simple Tips for Accessible Instruction in Higher Education. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20220324.EN

Our authors introduce themselves:

No Comments