At the start of the year, we asked you: What have you always wanted to know about teaching? The most frequently asked question was: should I provide my PowerPoint slides before my presentation or not?

A study by León and García-Martínez (2021) tried to answer this question.

Does it make sense to provide a set of slides prior to a class? If you ask students, the answer is clear: yes, please, absolutely! In the Teaching Analysis Poll (and likely other class evaluations), students are often critical if slides have not been provided in advance. A literature review by León and García-Martínez (2021) confirmed this pattern: students are firmly of the opinion that the provision of PowerPoint slides supports their learning process.

However, subjective convictions do not always stand up to a reality check: some ideas about teaching and learning arise more from myths than from evidence.

The currently available studies on this subject are unclear (León & García-Martínez, 2021): some studies see a clear advantage in providing PowerPoint slides up front. Other studies come to the opposite conclusion or show no tendency whatsoever. What these studies have in common is that they have looked for effects between different courses. The composition of participants may be very different. It therefore cannot be excluded that other effects (e.g. the previous knowledge of the students) might have influenced the study results. León and García-Martínez (2021) have therefore used a controlled study design within a single course. They looked for answers to the following research questions:

- What effect does the advance provision of PowerPoint slides have on the academic performance of the students?

- Can potential differences be explained through student engagement or the application of learning strategies?

- Does the provision of slides have an impact on the attendance of students in courses?

The study was carried out in a course in the field of Pedagogy at the University of Jaén (Spain). 173 students participated in the course, attendance was voluntary.

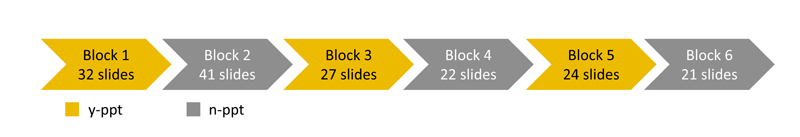

The content of the course was divided into six thematic blocks, for which a total of 167 slides were prepared. Through random selection, it was decided for which thematic blocks the slides would be provided in advance (y-ppt) and for which topics the slides would be used during in-class instruction but not provided to the students (n-ppt). Figure 1 shows an overview of the distribution.

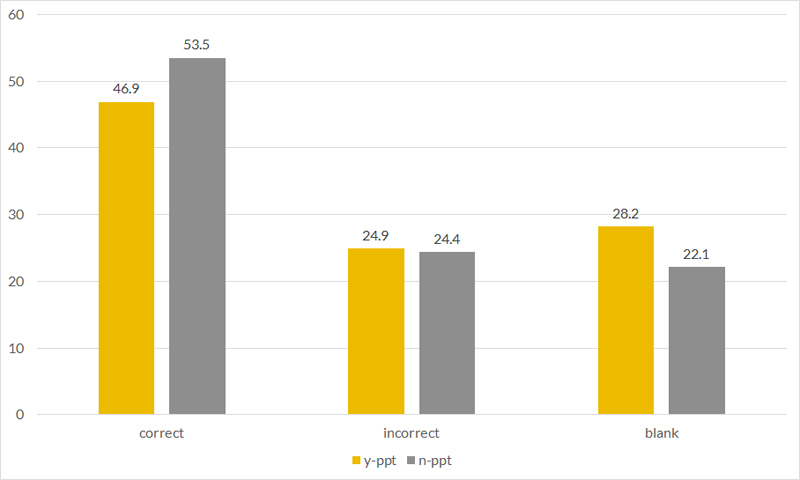

Weaker learning performance with PowerPoint slides provided

To test the knowledge gained, the students answered multiple-choice questions on each thematic block at the end of the semester (in addition to the actual module exam). The evaluation of the results showed a significant difference between the groups (x2(2) = 22.68, p<0.001). For the blocks for which the students received no PowerPoint slides, they answered more questions correctly (see Figure 2). The number of incorrect answers was independent of the provision of slides. More questions remained unanswered, however, for which the students had received PowerPoint slides.

This result was scarcely moderated by individual factors, such as student engagement and the use of learning strategies. Both factors were determined using standardized instruments in the middle of the semester.

Students achieved lower results in the knowledge test when the slides were provided and higher results when they did not receive any slides. This was independent of student engagement and the use of learning strategies. At the same time, students with average or higher scores for student engagement did better on the knowledge test than their classmates with lower values – independent of whether PowerPoint slides were provided for the topic or not. The same was true for students with a higher use of learning strategies.

PowerPoint slides replace attendance

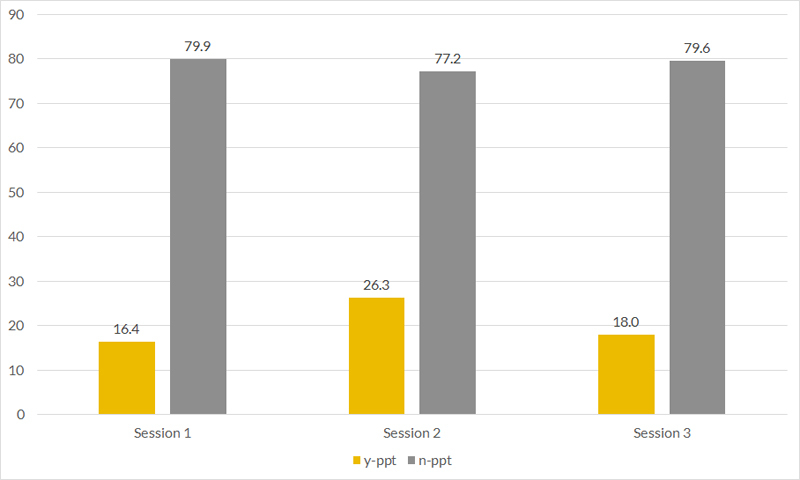

Attendance was checked at unannounced and randomly chosen sessions once per thematic block. From Figure 3, it is clear that the provision of slides encouraged the absence of students from the course.

While only around a fifth of the students participated in the in-person class for thematic blocks with PowerPoint slides, at least 77.2% of students were present for the topics without slides.

No more providing PowerPoint slides in the future?

At first glance, this study provides a clear result: The provision of PowerPoint slides in this study lead to increased absences of students and poorer results on knowledge tests. Previous studies (e.g. Crede et al., 2010) clearly showed that attendance is the best single predictor of successful learning. Lower attendance therefore explains the poorer performance of the students in the topics with PowerPoint material.

However, it is possible that other factors which could not be controlled for may have influenced the results. It is conceivable that concentration was reduced due to the provision of PowerPoint materials, or that the materials led to more superficial notes being taken.

These points would speak in favor of no longer providing slides.

At the same time, the learning process is too complex to be limited to these factors. In this study, it has already been indicated that the use of learning strategies and student engagement decisively influence successful learning – independently of whether slides were provided or not.

Ultimately, emotional and motivational factors also play a role. The provision of PowerPoint slides appears to give students a certain sense of subjective security that they already have the most important content. And many expect the slides as an essential part of any course. The (internal) announcement that they would no longer be provided generated – at least among our student helpers – absolute dismay.

As long as attendance can be ensured or encouraged in another way, the study provides no conclusive evidence, neither for the fact that the provision of slides significantly supports learning, nor for the fact that it hinders it. What appears to be more important – as it so often is – is how the material is designed and embedded into the curriculum.

The question “to provide slides – yes or no” will likely continue to be discussed between lecturers and students for a long time. Some things speak in favor of it, some against it. Ultimately, other factors aside from the provision of slides appear to have a more significant impact on successful learning.

What is your opinion on providing your slides? Share your experience on Twitter, Facebook or using the comment function.

Naturally you can pose more questions about teaching and learning in higher education all year long. We will try to provide evidence-based answers to your questions.

References

Credé, M., Roch, S. G., & Kieszczynka, U. M. (2010). Class Attendance in College: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Relationship of Class Attendance With Grades and Student Characteristics. Review of Educational Research, 80(2), 272–295. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654310362998

León, S. P., & García-Martínez, I. (2021). Impact of the provision of PowerPoint slides on learning. Computers & Education, 173, 104283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104283

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Hawelka, B. (2022, June 16). Providing Presentation Slides in Advance – Yes or No? Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20220616.EN

Birgit Hawelka

Dr. Birgit Hawelka is a research associate at the center for University and Academic Teaching at the University of Regensburg. Her research and teaching focuses on the topics of teaching quality and evaluation. She is also curious about all developments and findings in the field of university teaching.

- Birgit Hawelka#molongui-disabled-link

- Birgit Hawelka#molongui-disabled-link

- Birgit Hawelka#molongui-disabled-link