In the last few semesters, most of the teaching at universities had to be converted into digital formats. In the process, the focus shifted onto the courses’ self-learning phases in particular. Lecturers now stipulated exactly how students should work through the learning content online on their own so that they could prepare for a virtual, synchronous class that might follow. As a result, some of the students had the impression that the amount of subject matter and the time expenditure were significantly greater (Hawelka & Hilbert, 2020) than in previous semesters. This was not the case, however. Even before COVID, students should have prepared for in-person classes in autonomous self-learning phases or followed these classes up at home afterwards. However, the students were mostly able to decide for themselves whether or not to prepare for a course at home and if so, when and how. In the semesters during COVID, the lecturers now required them to deal with the subject matter on their own in a structured manner. The lecturers did so by posting very specific tasks in online learning environments and requiring submissions by a specific date.

By now taking over the structuring of the students’ self-learning phases with the help of online learning environments, the lecturers sometimes guided their students’ learning process to a considerable degree. So how can this guidance now be designed successfully and connected up with an in-person class?

Without support, the quality and therefore the effectiveness of self-learning phases tend to be low. The learning behaviour of many students does not match the “ideal picture” of a self-regulated learner (Hübner, Nückles & Renkl, 2007). This can have a negative effect on how a course proceeds overall and thus on the learning success of the students, however. If students are not prepared for an in-person class, it is not possible to build on previous knowledge. Therefore, the basic knowledge required often has to be taught first, with the result that there is not enough time left in the in-person class to process knowledge in depth or apply it. If students do not follow up in-person classes enough, this, in turn, often leads to gaps in knowledge remaining undetected. As a result, students are in danger of falling behind in their learning process and it is very difficult for them to catch up again (Hiltmann, Hutmacher & Hawelka, 2019). Unfortunately, it is not enough for lecturers to point out the significance of self-learning phases to their students. Instead, students’ self-learning phases frequently have to be guided with the help of suitable learning environments and appropriate behaviour on the part of the lecturers (Wrana, 2009).

Connecting up in-person classes and self-learning phases

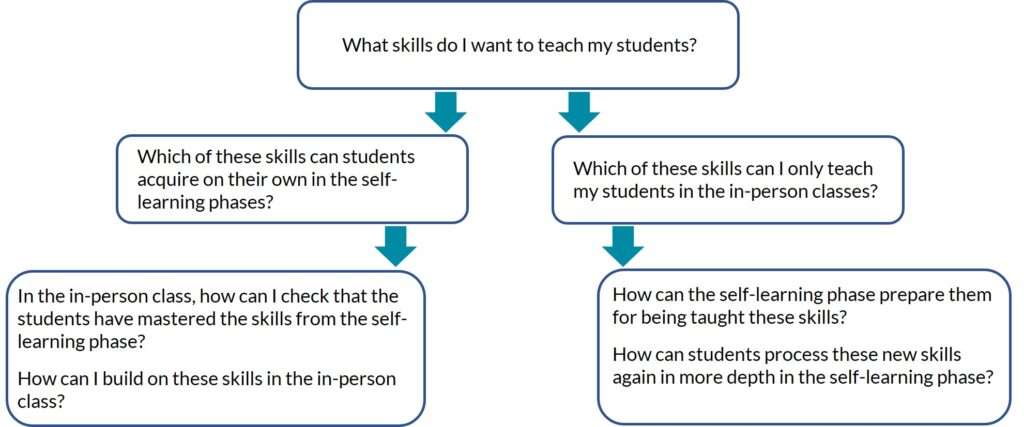

When planning and designing a course, lecturers need to connect up in-person classes and self-learning phases, dovetail their content and coordinate them systematically. Content that has already been prepared in a self-learning phase should not be repeated in its entirety in an in-person class, for example. At most, the in-person class should address misunderstandings or mistakes made in the self-learning phase. What is key is for the in-person class to build on the skills and level of knowledge gained in the self-learning phase.

Likewise, content taught in an in-person class should be processed actively during a subsequent self-learning phase rather than simply being repeated.

To determine which content should be taught in the in-person class and which in the self-learning phase, lecturers should find their own answers to the following questions:

Once the questions in Figure 1 have been answered, the planning of the individual classes and corresponding self-learning phases can commence. For both of these aspects it must, of course, be specified what subject matter is to be presented, when and how it is to be presented, and what methods can be used to process it actively.

Supporting the students’ learning process in self-learning phases

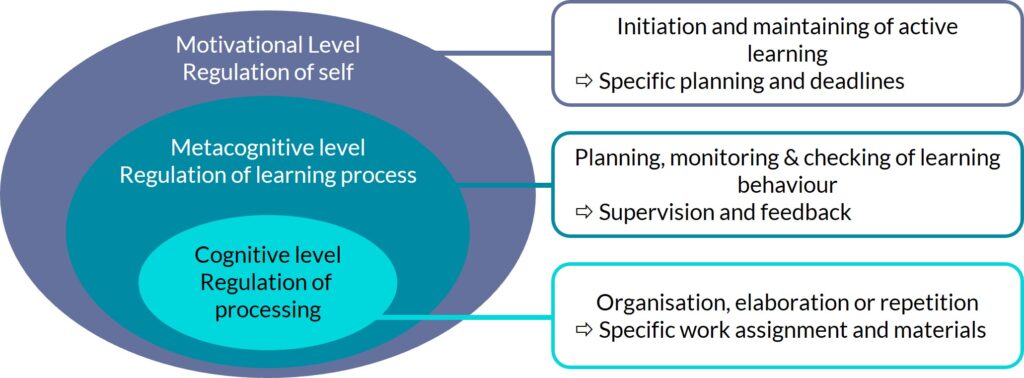

In the self-learning phases, students have to regulate the cognitive, metacognitive and motivational aspects of their learning process (Jansen et al, 2020). That means that they regularly have to initiate and maintain their learning process, and successfully apply adequate learning strategies depending on the learning content and the task. Figure 2 below shows the different regulation processes that the students go through during self-regulated learning. The figure also shows initial indications of how lecturers can help their students with the processes and how this support can be implemented practically.

By developing an appropriate learning environment for the self-learning phases which includes tasks, deadlines and offers of support and supervision, etc., lecturers take on part of the regulation of the students’ learning processes and take the pressure off them as a result.

Here, lecturers should proceed as follows:

1. Supporting the organisation, elaboration or repetition of the learning content

To enable the cognitive processing of learning inputs, the students have to deal with the learning content actively. They require specific work assignments and tasks in order to do this. The tasks need to contain clear information and prompts as to how the students should deal with the learning content:

- whether they should organise and structure the content according to a particular pattern;

- whether they should revise the content in a certain way;

- whether they should make a connection between the content and the knowledge they already have or establish interconnections between practice and the theoretical content.

What is important here as well, of course, is that necessary materials are made available or can be accessed.

2. Supporting planning, monitoring and checking of the learning behaviour

Depending on the task, thought should also be given to how the students need to be supervised and supported by the lecturers when working on the tasks. With some complex tasks, lecturers should also be available to talk to outside the in-person classes (e.g. during office hours), so as to be able to offer help. Opportunities for asking questions (e.g. including using a forum in the case of digital teaching) or extra meetings should be included in the planning, for example. To help the students check their own learning progress, lecturers should regularly give feedback on how the students have processed the tasks they were set (in this regard, see the blog post: There’s More to it Than Just “Good Job!” – The 7 Principles of Good Feedback. Individual feedback would be ideal, but you can also fall back on more general methods, such as summarising the most common misunderstandings or providing a sample solution. The method of peer feedback can also be used, but this should not be a substitute for feedback from the lecturers.

3. Supporting the initiation and maintaining of active learning

One important factor that affects the success of students’ self-learning phases is the motivation to learn. In order for learning to be able to happen successfully in these phases, students have to accept what they are being offered to learn. That means that they initially have to engage with the tasks and want to work on them successfully. Therefore, learning environments should consider factors affecting motivation to learn (see blog post “How Can Instructors Foster Student Motivation ?”) and be devised and designed by lecturers in accordance with these factors.

Apart from these factors which have an effect, it is absolutely essential to use deadlines in self-learning phases to set a regular schedule for when students need to hand in their work, what they should hand in, and how. That way, lecturers enable the students to learn regularly and prepare and follow up the in-person classes according to an appropriate schedule.

Students’ willingness to complete the self-learning phases successfully with the tasks assigned to them is also influenced by whether they see an additional benefit in doing so. That means that it must be clear to the students why it makes sense to prepare and follow up the in-person classes in this way. Lecturers can achieve this by communicating and presenting the intended learning outcomes of a course clearly. One good method to use here is the Advance Organiser (see the blog post “From (A)dvance To Organi(Z)er ”).

Lecturers should use these three processes as orientation when designing and supporting the self-learning phases. However, what the practical application then actually looks like has to be determined for each course individually depending on the group of students, the learning content and the frame conditions. The designing, organisation and implementation of a self-learning phase can be made easier with the help of digital learning environments. Many of the tools used in these environments offer a series of options for presenting learning content promptly and appropriately and processing it through a wide variety of activities.

Perhaps you have already had a little bit of experience with these. We would be happy if you would tell us about it using the comment function. Maybe you even have a tip or two which has meant that your self-learning phases have always worked particularly well. You are very welcome to share these with other lecturers using our comment function.

References

Boekaerts, M. (1999). Self-Regulated Learning: where we are today. International Journal of Educational Research, 31, 445–457.DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(99)00014-2

Hawelka, B. & Hilbert, S. (2020). Lehre im Corona-Semester. Ergebnisse einer Studierendenbefragung. Beitrag zum Tag der digitalen Lehre, Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13432.98565

Hiltmann, S., Hutmacher, F., & Hawelka, B. (2019). Selbstlernphasen Studierender unterstützen. In D. Jahn, A. Kenner, D. Kergel & B. Heidkamp-Kergel (Hrsg.), Kritische Hochschullehre. Impulse für eine innovative Lehr-Lernkultur (S. 305-322). Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-25740-8_16

Hübner, S., Nückles, M., & Renkl, A. (2007). Lerntagebücher als Medium des selbstgesteuerten Lernens – Wie viel instruktionale Unterstützung ist sinnvoll? Empirische Pädagogik, 21, 119-137.

Jansen, R. S., van Leeuwen, A., Janssen, J., Conijn, R. & Kester, L. (2020). Supporting learners’ selfregulated learning in Massive Open Online Courses. Computers & Education, 146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103771

Wrana, D. (2009). Zur Organisationsform selbstgesteuerter Lernprozesse. Beiträge zur Lehrerbildung, 27, 163-174. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:13717

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Rottmeier, S. (2021, September 9). Self-learning phases – An important component of EVERY course. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20210909.EN

Stephanie Rottmeier

- Stephanie Rottmeier

- Stephanie Rottmeier

- Stephanie Rottmeier

- Stephanie Rottmeier