As Martin Luther once said: “If you preach about the article of justification, the people sleep and cough; but if you begin to speak of histories and examples, they prick up both their ears, stay quiet and listen intently” (Weimar edition of Luther’s works, Table Talk 2, No. 2408b). So even that powerfully eloquent reformer had to grapple with a phenomenon with which teachers and lecturers in the 21st century are also likely to be somewhat familiar: the magic of stories.

Why is storytelling so appealing? Because it presents all kinds of contents in a way that is easiest for the human mind to process: namely, the way it perceives reality itself – as a series of events in time and space that are causally interconnected and are accompanied by emotions. Telling a story is “mindlike speaking” (Mellmann, 2012, p. 35).

So what could be more obvious than to mix business with pleasure and make storytelling bear fruit in the context of teaching and learning? As a method, i.e. designing and applying stories effectively in teaching, storytelling can achieve the following goals, for example:

- directing attention

- setting narrative anchors, i.e. making it easier to build and retrieve knowledge

- effecting a positive change in attitude to a topic

- providing low-threshold access

The way to create compelling stories for teaching

First of all, it is a question of choosing the topic around which a story should evolve. What specific contents do you want to anchor? What learning outcomes should be achieved? You can also already determine what the story’s function should be in a didactic setting: do you want to use it to introduce a topic? Or do you want to use it at the end so as to transfer what the students have learned? It could also possibly be used in the development phase if you were to interrupt the story at suitable points and combine it with assignments you gave to the students. As soon as the topic and the learning outcomes have been decided, you can start developing your storytelling.

Step one: Narrative potential

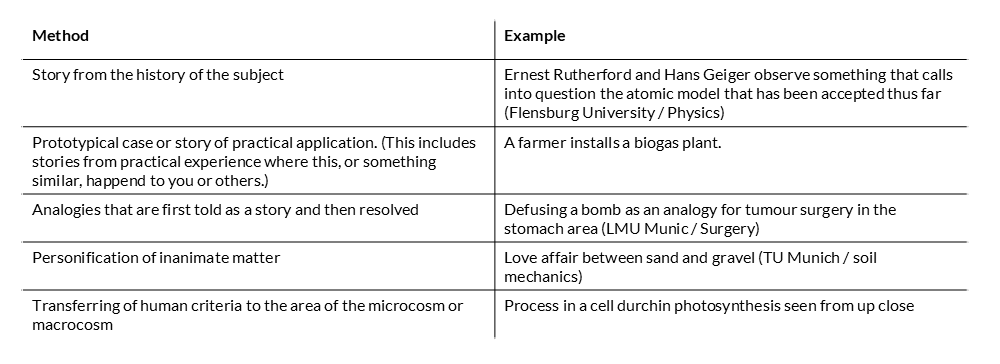

In the many years of my own practice of storytelling and as the result of many seminars on teaching and learning at university, five approaches have crystallised that can encapsulate almost any topic in a story that is easy to tell.

The examples below are from people who have taken part in my seminars, experts in their field who have then translated their experience into very good stories:

All of these approaches have definite advantages and disadvantages and are not all equally suitable for the specific subject matter being taught. In practical experience, however, the bundle has so far proved robust: therefore, at least one or two possibilities for narrativisation were found for every topic brought along.

Step two: Clear structure

What is presumably also anchored in evolution is the simplest and, at the same time, prototypical structure of many stories. This structure is essentially composed of three parts – which is illustrated here by an example of the story from history approach:

- an initial situation that is in relative equilibrium (often a routine): In 1747, James Lind is sailing on the high seas as a ship’s doctor with the Royal Navy;

- a disruption of this relative equilibrium due to a problematic development, a conflict, mounting danger or a challenge. Twelve sailors fall ill with scurvy – a disease which was considered incurable at that time and mostly ended in death;

- the creation of a new relative equilibrium that can be judged as better or worse than the initial situation: Thanks to one of the first examples of controlled testing to be carried out in the history of medicine, James Lind finds a cure – citrus fruits.

Did you notice? Strictly speaking, even the quote from Martin Luther given in the introduction already mirrors the minimal structure described. Initial situation in equilibrium (sermon on theological concept), disruption (coughing / falling asleep), creation of a new equilibrium (by telling stories).

Step three: Meat on the bones

As such, the structure constitutes the necessary prerequisite for a story to work, but it is only an indication of the contents, a skeleton, so to speak, with no life in it as yet. To achieve the quality of mindlike speaking, which is mentioned above, and therefore succeed in enabling the minds of the audience to process what they hear effortlessly, we need a sequence of clear, understandable pictures that can fill the dramatic structure with life.

But where do you find those pictures? Clear and simple: in ourselves. The capacity to use our imagination – a capacity we all have as human beings – means that we can access our creative side, our powers of imagination. How do I picture James Lind and his life as a ship’s doctor? What do the symptoms of advanced scurvy look like? How does Lind feel when he makes his discovery? If it helps, you can close your eyes and try to picture it. What you imagine can take very different, individual forms, which can be visual, auditory or abstract.

After perceiving them consciously, you can record them and transfer them to different media depending on how you ultimately want to implement the story: as a spoken or written text, a comic or film, or a role play, etc. The simplest way to present a story, and one that takes the least effort, is still to tell it verbally, either in person or on video.

The more often you take the three steps described here, the easier you will find it. If reading this has sparked your desire to tell stories: start with ones that are short and sweet, enjoy your success and then keep building on that. Anything is possible, all the way to structuring the lecture narratively for an entire semester. Here’s to your students pricking up both their ears, staying quiet and listening intently!

References

Ellrodt, M. (2017). Die Faszination mündlichen Erzählens – Ursachen und Einsatzmöglichkeiten. In N. Hübsch & K. Wardetzky (Hrsg.), Zeit für Geschichten – Erzählen in der kulturellen Bildung. Schneider.

Lipman, D. (1999). Improving your storytelling: Beyond the basics for all who tell stories in work or play. August House.

D. Martin Luthers Werke. Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Abteilung Tischreden, Weimar 1883ff.

Mellmann, K. (2012). Is Storytelling a Biological Adaptation? Preliminary Thoughts on How to Pose that Question. In C. Gansel & Dirk Vanderbeke (Hrsg.), Telling Stories. Literature and Evolution. (S. 30-49). de Gruyter.

Olson, R. (2015). Houston, We Have a Narrative. Why Science Needs Story. The University of Chicago Press.

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Ellrodt, M. (2022, December 8). Storytelling in three steps – How to teach and fascinate people using stories. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/zhw/20221208.EN

Martin Ellrodt

Martin Ellrodt is a stage storyteller and storytelling educator with performances and seminars on four continents and in four languages.