When it comes to teaching, many only think of seminars or lectures. But office hours also make up an important part of a university lecturer’s day-to-day that is often underestimated. They are a valuable way for lecturers and students to be in contact. When preparing for and holding office hours, there are several points to bear in mind so that you can realise their potential.

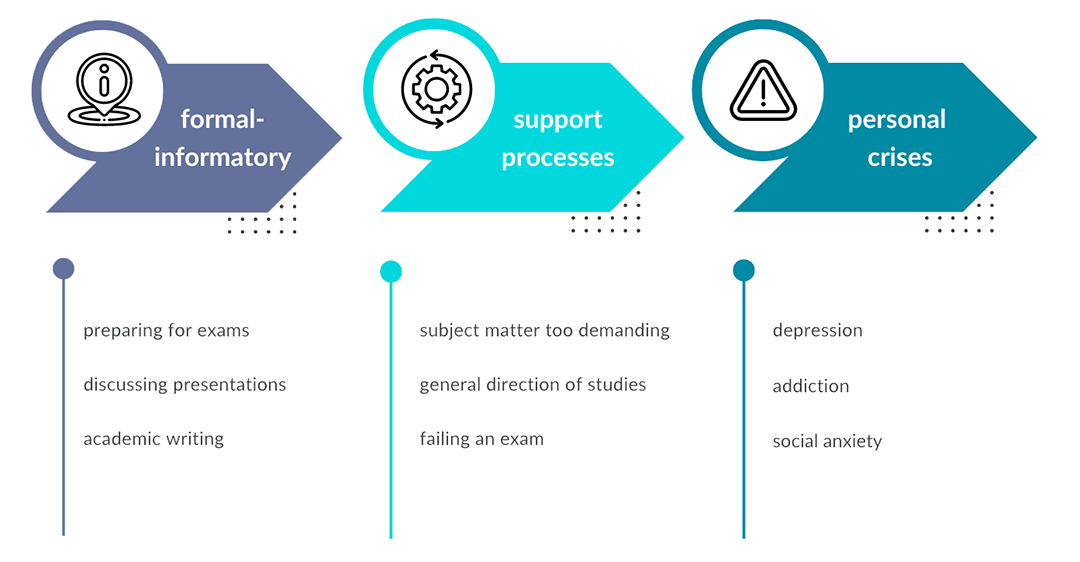

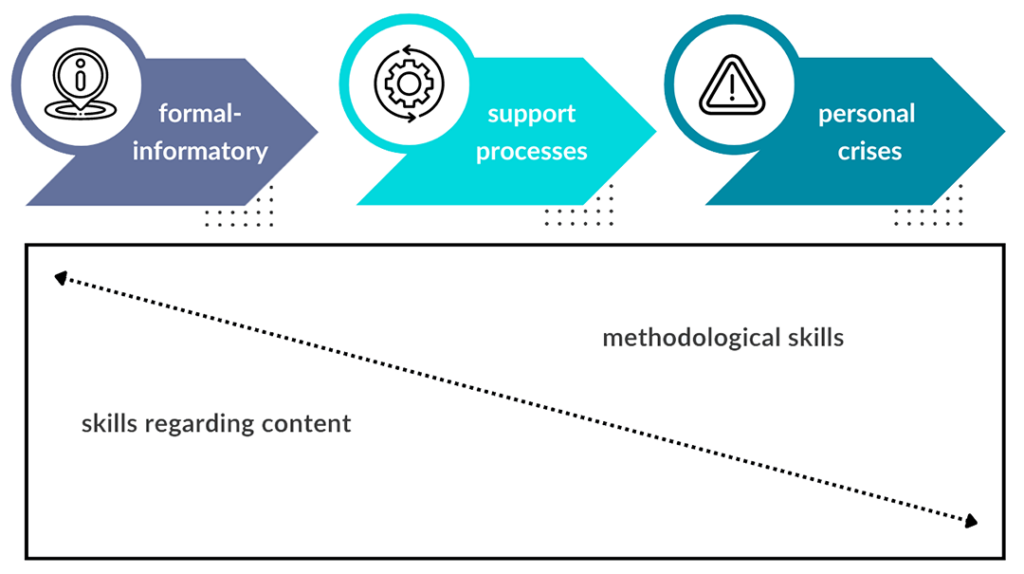

There are a multitude of topics involving students’ studies that they would like to talk to you about during your office hours. These topics range from discussing presentations to subject-related problems all the way to fear of exam situations. Depending on the occasion, the various topics can be categorised as formal and informatory, supporting students in their process, or personal crises. The figure below shows some examples.

This categorisation is not only important in theory but also relevant in practice, as the different reasons why students come to office hours require different conversation skills.

In formal, informatory conversations (on the left of the graphic), lecturers need the corresponding skills regarding content, as here they are mainly imparting information.

In conversations about personal crises on the other hand, it is primarily a methodological skill in counselling that is required, as the focus is more on acknowledging feelings and interpreting what the other person is expressing. Both skills can be necessary in conversations where students are receiving support in their process. The topics of these conversations definitely require a whole list of corresponding information, but, depending on the direction they take, can also address personal situations of a critical nature. Students may say that the reason they are going to office hours is that they have failed a written exam, for example. In this case, on the one hand they would certainly require information about the resit and want to talk about improving their current learning behaviour, but on the other hand it could come up in conversation that the reason they failed the written exam was due to a certain degree of exam nerves. A conversation about exam nerves requires a methodological skill in counselling, however (see Figure 2).

At the start of their office hours, university lecturers should be aware of those topics for which they are the right person to come to and the topics which would be better dealt with by a different person or department. What is important here is that particularly topics categorised as personal crises should only be dealt with by professional counselling services. If you notice that students are coming to your office hours with topics of a critical nature, you can refer them to the Central Department for Course Counselling at the University of Regensburg:

Good preparation is the nuts and bolts

So that you can already clarify in advance which topics students want to discuss with you, you should ask the students to prepare for your office hours. The students should tell you in beforehand

- what their reason is for coming to your office hours. Therefore, they should communicate their key questions and desires.

- what the students have already done to solve the problem on their own, and

- what expectations they have of you as a lecturer.

That way you can already determine beforehand whether you are the right person to talk to about the problem at hand.

However, as a lecturer you should also find answers to a few questions in the run-up.

First of all, you need to establish when the students can contact you. Should you hold your office hours regularly (e.g. weekly)? If so, how do you communicate to the students when your office hours are?

Or should students arrange individual appointments with you? If so, how can the students arrange such appointments?

You subsequently need to decide on a medium. Do you want to hold your office hours in your office in person or virtually on Zoom?

The advantages of direct (synchronised) conversations like this are that questions can be answered directly and follow-up questions asked. In the run-up, you should have a think about how the room should be designed (Weinberger, 2013). For conversations that take place in person it is advisable to design the room in a way that supports this and avoids distractions (e.g. phone call diversion, relevant information on the office door, etc.) For conversations that take place on Zoom you need to consider how much of the room you want the students to be able to see and adjust the camera background accordingly.

Even if is not yet common practice, it would definitely be conceivable for office hours to be organised in an asynchronous manner (Stanik & Maier-Gutheil, 2020) – by email or through forum posts, for example. As communication takes place without any time pressure, you can give sufficient thought to your own posts and answer questions extensively. Besides that, you can also provide further information material quickly and straightforwardly (e.g. attach or link it).

For asynchronous conversations it is important to provide some information beforehand:

- How soon can the students expect a reply to their request?

- How much material must/should the students attach to their requests? Their answers to the tasks, or highlighted parts of the text they haven’t understood, for example.

- To what extent can the students’ posts on forums be seen by others (e.g. fellow students or other lecturers)?

In addition, you should ensure that your language is personal. Even if the communication takes place in writing, the framework is very much as it would be in a verbal conversation. This includes an opening message in the forum that invites students to use the forum as your office hours.

How can you structure conversations in your office hours?

So that your office hours can work efficiently and productively, conversations have to be structured wisely and be based on a pattern of procedure. The structure according to the Munich model of conversation techniques (“MMG” model, Gartmeier, 2018) is particularly suitable for formal, informatory conversations. This model is based on appreciation, constructive cooperation and finding solutions in conversations you are having. In conversations with students, your basic attitude should be one of appreciation, in that you take the students’ opinions seriously even if you don’t share them. Furthermore, it is important for it to be clear to both sides that if there is a problem, lecturers can provide support as experts in the subject but will not present complete solutions. In addition, you need to make the structuring of the conversation transparent to the students. That way you can guide the conversation in a way that is outcome-orientated. The “MMG” model consists of a total of six steps that make it possible to structure the development and process of a counselling session well (Gartmeier, 2018).

1. Greeting

At the start of the conversation, give your students a friendly welcome and show interest in them and the coming conversation (e.g. by diverting your calls or putting your phone on mute). Try to get a feel for your students’ current emotions, and address these as well.

2. Assessing the actual situation

Subsequently, try to gain a differentiated understanding of the current problem and give the students the subject-specific information that is relevant to that. When you do so, communicate your own observations or stance as well and acknowledge the situation the students are in (e.g. difficulty dealing with specialised literature in the first semester).

3. Defining the situation as it should be

Now you should summarise what the goals you worked out together in your last conversation are and by when the students should implement them.

4. Introducing and weighing up suggested solutions

Depending on the goals set, you and the students should generate and weigh up ideas and ways to come to a solution together. Here, you also discuss the approaches the students have taken to finding a solution so far.

5. Decision and agreement on its implementation

Directly after deciding on a way to come to a solution, you should plan its specific implementation together and agree on how the students should now proceed. Offer your advice and support in the process.

6. Ending the conversation

To end the conversation, try to create an encouraging and motivating situation to finish off. Ask your students if they are satisfied with the conversation and the specific plan of implementation and offer the option of further conversations.

The following video (in German language only) shows the application of the “MMG” model in a situation during office hours.

What has been your experience of office hours? What tips and tricks do you use for your office hours to be effective? Please feel free to share your experiences using the comment function or LinkedIn.

References

Gartmeier, M. (2018). Gespräche zwischen Lehrpersonen und Eltern. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Stanik, T. & Maier-Gutheil, C. (2020). Online-Beratung – Formate, Anforderungen, Befunde. Kontext, 51(2), 110–122.

Weinberger, S. (2013). Klientenzentrierte Gesprächsführung. Lern- und Praxisanleitung für psychosoziale Berufe. Weinheim und Basel: Beltz Juventa

Wiesmann, B. & Schmucker, T. (2007). Studierende ziel- und lösungsorientiert beraten. In Hawelka, B., Hammerl, M. & Gruber, H. (Hrsg.), Förderung von Kompetenzen in der Hochschullehre (S. 209-219). Kröning: Asanger.

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Rottmeier, S. (2024, June 13). Office hours – more than a meet-and-greet. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20240613.EN

Stephanie Rottmeier

- Stephanie Rottmeier

- Stephanie Rottmeier

- Stephanie Rottmeier

- Stephanie Rottmeier