Based on Barney Stinson’s credo “new is always better”, when it comes to teaching at universities you might also think that it would be exactly the right framework for you to try out new didactic tools or approaches. The apparent reasons for this are self-evident: universities are places of research, which are constantly measured by its innovativeness. And as lecturers are simultaneously researchers as a rule, it should be a matter of course for them to demonstrate this personal connection to research in their teaching as well and to use innovative ideas and findings from research in teaching and learning actively in their own teaching. So why should new not always be better? There is likewise an important reason for this: stimuli for integrating innovative ideas in teaching at universities (no matter whether it is a degree programme, module, course or individual meeting) should always take the teaching context into account as well. Therefore, one ought to clarify the specific problems and challenges that would be addressed by the innovative stimulus or the advantage that would come from an innovative solution (e.g. for students). Without good reasons like these, however, innovative ideas tend to be harmful, as they needlessly replace routines that work well.

Innovative teaching is a relative term

The term “innovative teaching” at universities might initially make you think of prizes for good teaching or of projects aiming to foster innovative higher education. Both examples are proof of the fact that universities and their lecturers are keen to ensure and further develop the quality of the teaching. At the same time, however, it is debatable whether this image of innovative teaching appeals to all lecturers, as it simply sets the bar too high.

What does not become clear here is the crucial importance of the context in which lecturers and students find themselves in different departments and degree programmes. If you first ask about the specific problems and challenges that have to be overcome in order to make good teaching possible, you arrive at a much broader and more open idea of what innovative teaching can be. In line with an established definition of the concept of innovation coined by organisational research (see West & Farr, 1989), innovation in higher education is always about implementing ideas that bring something new to a specific teaching context but that also fit the day-to-day aspects of teaching in this context – which is why they are suitable for making a positive contribution to the quality of the teaching in this context in the first place. From this we can conclude that it is not the size of the innovative idea that matters. A small but key change to a seminar concept can be just as innovative as the radical restructuring of a module or degree programme. In addition, taking the teaching context into account means that innovative teaching is not exclusively associated with absolute novelty – in terms of aligning teaching with the latest findings and (sometimes also) trends in research in teaching and learning – but becomes a relative concept: the more problems there are in teaching that need to be solved and the more dissatisfied lecturers and/or students are, the easier it is for simple ideas to become innovative solutions very quickly.

Idea push or need pull? Both!

Very closely linked to these considerations concerning the relationship between (potentially) innovative ideas and the application context are two opposing modelling assumptions with regard to the origin of innovations: idea push (originally: technology/science push) and need pull (see Marinova & Phillimore, 2003). On the one hand, the idea-push model assumes that innovative solutions are triggered by new (scientific) findings. Applied to the teaching context, this means that changes to established teaching concepts and methods come about when scientific findings regarding good teaching find their way into teaching at universities (e.g. via journals, conferences or social exchange). The need-pull model, on the other hand, tends to see the causes of the emergence of innovative solutions as lying in practice and in the needs and demands that exist there. In the teaching context, therefore, innovative solutions would be triggered if problems in courses or degree programmes become visible or become apparent (e.g. because the course of a seminar no longer works or meets with rejection or because people feel overwhelmed or dissatisfied).

Both models contain important practical implications: the idea-push model highlights the important role that ideas can play in triggering innovations in teaching. The need-pull model, on the other hand, emphasises that the actual practical needs must always be taken into account as well. A sensible strategy for teachers could therefore be to keep up to date with new findings and concepts as well as current topics and trends in order to be able to respond to problems and challenges as needed as soon as they arise.

Being innovative in teaching: So how does that work exactly?

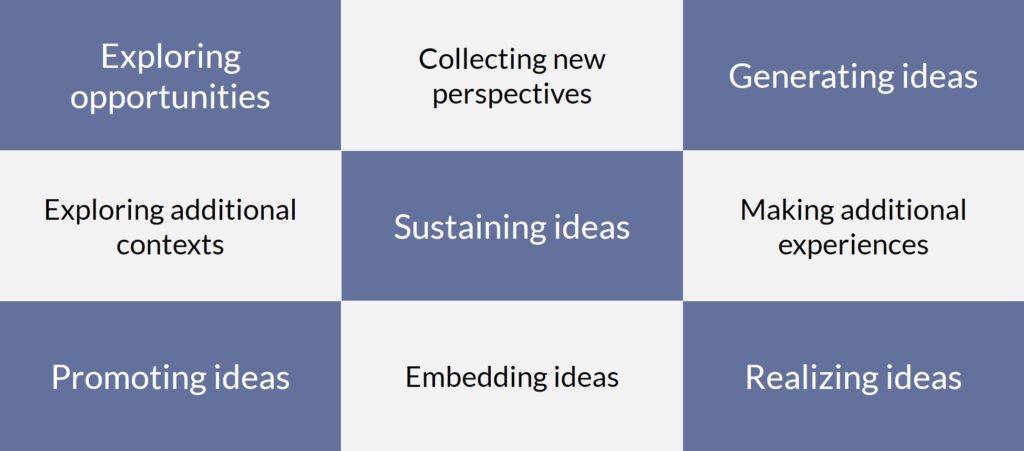

In industrial and organisational psychology, such efforts by teachers are referred to as innovative work behaviour (Janssen, 2000; Scott & Bruce, 1994). Building on models of the creative process (Amabile, 1988) and of organisational innovation processes (Kanter, 1988; West & Farr, 1989), innovative work behaviour summarises all the individual contributions required to successfully develop an innovative solution for a specific practical context. As presented in Figure 1, the following aspects of innovative work behaviour can be distinguished (see Lambriex-Schmitz et al., 2020; Messmann & Mulder, 2017):

Exploring opportunities: This is a question of keeping up to date with processes and events at work (i.e. in the organisation, team or personal work processes). In turn, this provides the opportunity to recognise existing or emerging needs and problems and the associated necessity or opportunity for change and improvement in a timely manner.

Generating ideas: To be able to respond adequately to an existing need for change, suitable ideas need to be developed that demonstrate a meaningful solution to the underlying practical problem. Typical approaches here include, for example, researching a wide variety of sources relevant to the subject or topic, and social exchange with colleagues or in your own professional networks.

Promoting Ideas: Being able to initiate and realize a process of change requires all kinds of physical and mental resources, such as time, money, a general legal framework or resilience, without which no planned change would be feasible. It is therefore important and helpful to work together with people who actively contribute their time or use their organisational influence because they believe in the idea. Of course, the level of support required directly depends on the ideal size of the planned innovation and the extent of the impact in the work context: the smaller and more contextually limited the planned change is, the more likely it is that even single individuals can make a big difference.

Realizing Ideas: In order for ideas for changes to become visible and effective, they really need to be developed and applied or implemented in practice as well. This can occur in several cycles: from a finalised concept (or prototype) to one or more test runs to its complete and sustainable implementation in practice. On the one hand, it is a question of gathering experience regarding the usefulness of the innovative solution and then using this directly for the iterative further development of the solution. On the other, it is a question of creating something tangible that can be used to convince other people of the advantage of the innovation.

Sustaining Ideas: The visibility of an innovative solution, on the other hand, is crucial in order to expand the support for the innovation, develop further prospects and ideas, and discover further opportunities for implementing the innovation. The exchange in the personal work environment (e.g. in a team, work group or department) typically plays a key role here. In addition, the spreading of an idea within the organisation and beyond its boundaries contributes to its becoming anchored sustainably. Ultimately, such efforts ensure that once implemented, innovative solutions become useful and sustainable routines.

The creation of sustainability can therefore be understood as the continuation of the first four aspects of innovative work behaviour: by exploring additional contexts within and outside your own organisation, similar or additional needs for change may become apparent. In turn, the resulting exchange goes hand in hand with the collecting of new perspectives on problems – which also increases the spectrum of ideas. Furthermore, the expanded social sphere of action leads to the increase in the potential for support and thus facilitates the making of additional experience in other contexts, which both contributes to the further development of existing ideas and enables ideas to be embedded in the organisational context and beyond.

Routines and innovations are not contradictionary in terms

As indicated in the last paragraph, innovative solutions are only innovative until they are successfully anchored in practice and develop their usefulness sustainably there. Then innovations become routines – which is not without a certain irony, as innovations and routines are often construed as opposites. This apparent contradiction is due to the ambivalent nature of routines themselves: on the one hand, routines (in teaching, for example) are viewed as something negative that is stuck in the past and therefore represents an obstacle to change, as it were. Hence, the notion that “lecturers who always do everything the same way are not good lecturers” is certainly not uncommon among students and also among lecturers themselves. The phrase that routines have to be broken up in the innovation process likewise attests to their bad reputation. On the other hand, however, routines also have a positive connotation because they are equated with personal experience, which in turn is connected to the assumption that experienced people can improvise and come up with something at the drop of a hat. The positive underlying characteristic of routines is that they require few cognitive resources of an experienced person due to their recurrent and predictable nature, thus creating space for something new (Hoeve & Nieuwenhuis, 2006; Ohly et al., 2006). Routines therefore offer lecturers, for example, the opportunity to think about changing or further developing their courses.

In addition to this fundamental connection between routines and innovations, the role of the context outlined at the beginning also results in lecturers taking personal responsibility for recognising whether there is an opportunity to optimise efficiency (by establishing and using routines) or whether it is necessary to respond to an existing need for innovation, depending on the situation (Mylopoulos et al., 2016). If lecturers come to the conclusion that the general framework of their teaching (e.g. number of students, module regulations, content preferences, student reactions, etc.) is stable and the learning success is still a given, they should tend towards acting as what one might call routine experts and dispense with unnecessary changes. If, on the other hand, lecturers observe that the general framework of their teaching or specific courses has changed and that routines no longer work in some areas, they need to behave as adaptive experts and respond to the need for change they have discovered with innovative solutions – by using a new didactic approach or offering new content, for example.

Five simple tips to keep your own teaching “fresh”

So what should lecturers do so that they can either let their routine play out or respond appropriately to any need for change that is required and do so at the right moment?

- Regularly check whether everything is going well – with yourself, with students and with colleagues; that way you will see which areas of your own teaching might require a change or that everything can remain as it is.

- Observe how others do it and realise that there are probably already good ideas and solutions there with regard to the challenges and problems in your own teaching; innovative teaching simply means that you implement ideas that are new in your own teaching context and that are suitable for improving something there.

- Make contacts and cultivate them – no matter whether you are more of a networker or prefer a small number of close contacts; as implementing changes in your own teaching (or in degree programmes) often requires the support of others (whether that be in the form of material resources, active participation or organisational support), a network can make many things easier and radically increase the feasibility of implementing an innovative idea.

- Set goals that are motivating and achievable – if you have spotted a need for change and already have a suitable idea or solution in mind, it is important to ask yourself what is actually feasible; although implementing ideas implies that you are open to risk and uncertainty, that uncertainty can be reduced if you pursue ideas that fit in with your own teaching philosophy and can be integrated into existing routines.

- Tell others about it – the “durability” of innovative solutions in teaching depends not only on whether they make a positive contribution but also on how well they are embedded organisationally; if others take up an innovative solution, that multiplies the experience (and thus the possibility of developing the solution further) and increases individual motivation to persist and have the innovation become a routine.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, 123–167.

Hoeve, A., & Nieuwenhuis, L. F. M. (2006). Learning routines in innovation processes. Journal of Workplace Learning, 18(3), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620610654595

Janssen, O. (2000). Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317900167038

Kanter, R. M. (1988). When a thousand flowers bloom: Structural, collective, and social conditions for innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, 169–211.

Lambriex-Schmitz, P., Van der Klink, M. R., Beausaert, S., Bijker, M., & Segers, M. (2020). Towards successful innovations in education: Development and validation of a multi-dimensional innovative work behaviour instrument. Vocations and Learning 13(2), 313–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-020-09242-4

Marinova, D., & Phillimore, J. (2003). Models of innovation. In L. V. Shavinina (Ed.), The international handbook on innovation (pp. 44–53). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Messmann, G., & Mulder, R. H. (2017). Proactive employees: The relationship between work-related reflection and innovative work behaviour. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 141–159). Dordrecht: Springer.

Mylopoulos, M., Brydges, R., Woods, N., Manzone, J., & Schwartz, D. (2016). Preparation for future learning: A missing competency in health professions education? Medical Education, 50(1), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12893

Ohly, S., Sonnentag, S., & Pluntke, F. (2006). Routinization, work characteristics and their relationships with creative and proactive behaviours. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(3), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.376

Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 580–607. https://doi.org/10.2307/256701

West, M. A., & Farr, J. L. (1989). Innovation at work: Psychological perspectives. Social Behaviour, 4(1), 15–30.

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Messmann, G. (2025, January 16). Innovation in teaching: Why something new is (not) always better. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20250116.EN

Gerhard Messmann

Dr. Gerhard Messmann is a lecturer in at the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Regensburg. As a lecturer in the Bachelor’s and Master’s degree programmes in Educational Science, he offers courses on topics such as learning and motivation theories or the analysis and development of learning environments. In his research, he deals with different aspects of work-related proactivity, such as innovative work behaviour, informal learning or reflection at work. His work has been published in international journals like Vocations and Learning, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Human Resource Development Quarterly and Computers & Security.