Teach a group of university students today, and you will quickly realize how much they rely on social media platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok to understand the world. Thanks to algorithms driven by likes and shares, videos on these platforms can travel around the world while serious scholarship is still putting on its shoes. How can we train students to be responsible consumers—and even producers—of content for such video-based platforms? And how can we, as seasoned scholars, learn a thing or two about scholarly communication from the most successful content creators out there on said platforms?

The experimental course “History Lab”

The generous support of the “Freiraum2023@ur” initiative allowed me to explore these questions in an experimental course that took place during the 2023-2024 winter semester, “History Lab: Mit digitalen Archiven forschen und wissenschaftliche Kurzvideos produzieren am Beispiel der digitalisierten Archive des Völkerbundes.”

Students had to learn three distinct competencies: (1) the history of the League of Nations and the history of the interwar period; (2) how to do research in the largest digitized archive in the world, across a source base in English, French, and other languages; (3) use these former skill sets to script, record, and produce a video about the history of internationalism. That’s a lot to cover in only three and a half months!

1. History of the interwar period

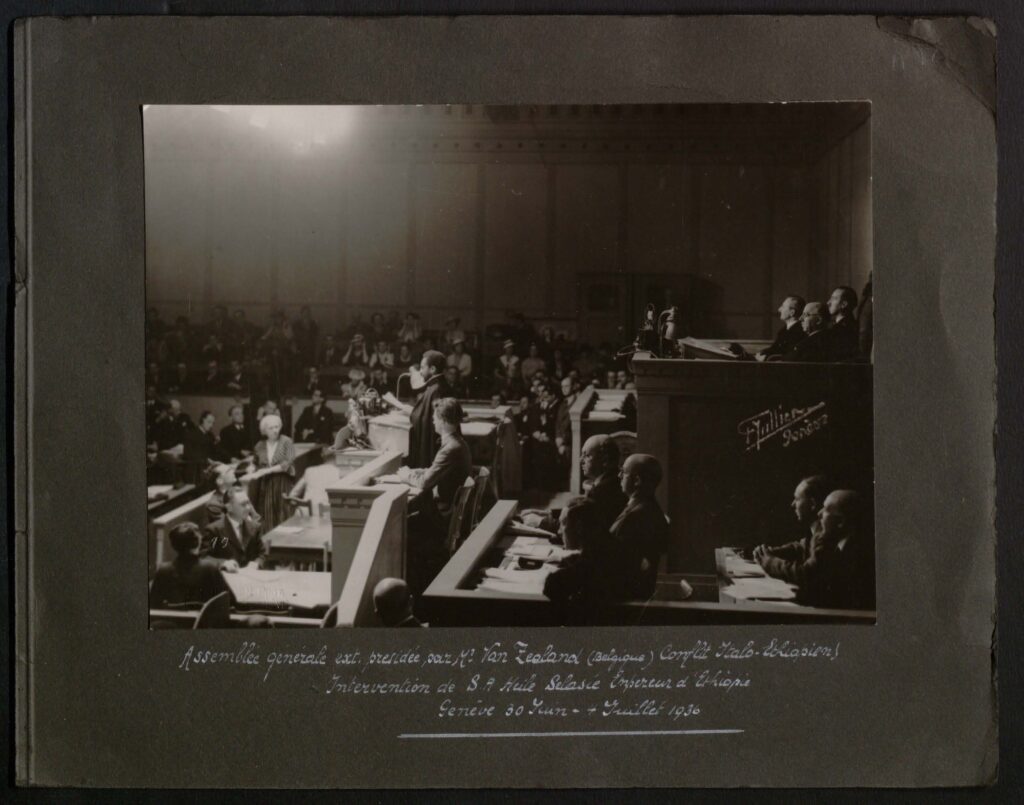

In the class, we focused on the history of the League of Nations, the world’s first international organization and the predecessor to the United Nations. The League of Nations has become a popular topic for international historians, since the men and women at the League faced challenges like pandemics and refugee crises familiar to us today. At a time when the liberal international order is showing severe signs of stress due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, understanding the history of prior attempts toward international cooperation could scarcely be more timely.

2. Research in the largest digitized archive in the world

What makes the League especially interesting for scholars like me, however, is that its archives—containing over 14 million pages of materials—have been completely digitized, thanks to private Swiss donors. This means that rather than traveling to the Palais des Nations on the shores of Lake Geneva, scholars and students can access virtually any materials concerning the world’s first experiment in governing the world.

Among these documents are, moreover, not only reports and letters, but maps, photographs, and caricatures that can allow historians to bring the past to life. Many of these materials are out of copyright and can easily be turned into the building blocks for videos that can help us understand the historical precedents for international cooperation today.

3. Script, record, and produce a video

So, thanks to resources like the video studio at the Center for University and Academic Teaching (ZHW) and video editors like Camtasia and DaVinci Resolve, students and teachers are limited only by their creativity if they want to make videos about this important chapter in modern history. It was, then, with a small but engaged group of students that I carried out this experimental course over the winter semester, both to introduce students to the history of the League of Nations and to teach them how we might find a balance between the “slow food” approach of traditional scholarship, on the one hand, and the “fast food” approach of short video-based social media, on the other hand.

From Idea to Course

These three learning priorities shaped the structure of “History Lab” during the 2023-2024 winter semester. Our first sessions covered the history of early attempts at international organization, such as the Congress of Vienna, and the founding of the League of Nations in early sessions. Several subsequent sessions exposed students both to challenges in international affairs (refugees, disarmament, and global public health, for instance) to which the League devoted itself. For these sessions, recent works like Mark Mazower’s Governing the World and Susan Pedersen’s The Guardians, a study of the League of Nation’s quasi-colonial mandate system, helped us strike a balance between big-picture narrative and the granular view offered by sources in the archive. Still other sessions introduced students to the major security crises of the 1930s, such as the Japanese invasion of Manchuria (1931) and the Italian invasion of Ethiopia (1935-1936) that revealed the League’s promise of collective security to be a myth.

Along the way, small exercises embedded in these thematic and historical sessions introduced students to the many digital resources they could use for their eventual video. The most important one was, of course, LONTAD, for the League of Nations took responsibility for monitoring pandemics and issuing passports for stateless persons. Other portals, like the Deutsches Zeitungsportal and ANNO, a historical newspaper database run by the Austrian National Library, allowed students to monitor how German-language newspapers made sense of a world in crisis.

At the same time, I realized that students had to be exposed to successful and less successful examples of historical documentaries if they were to realize their own visions in front of the green screen. So, amid my mini-lectures and discussions of secondary scholarship on the League of Nations, our sessions often examined the narrative strategy of historical documentaries like Ken Burns’ The Vietnam War, as well as shorter formats such as Terra X’s “MrWissen2go Geschichte” and “Ein Tag in …” In our discussions about these video formats, we examined how historical documentaries deploy both experts and moderators to communicate their message. We saw, moreover, how difficult it can be to do justice to ideas like internationalism, or complex conflicts like the Italo-Ethiopian War, in the short time we had planned for our videos.

But in order to really think about how to turn our ideas and the sources into video, we also spent several sessions at the ZHW’s studios and in the University of Regensburg’s Rechenzentrum to learn how to use DaVinci Resolve to produce videos that we had filmed. Other sessions back in our primary classroom focused on rights and permissions for music and sound effects, so that we could safely share our videos and make them public.

Several months after running the course, what have I learned?

Reflections on the course: teaching “what” vs. teaching “how”

One lesson from “History Lab” is that integrating digital archives and multimedia based final assignments means that I had to think about how to develop learning goals across multiple dimensions.

I felt more than comfortable teaching students about the history of the League of Nations and conflicts like the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, or the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, that led to the League’s demise. But in order to really reach my second and third learning goal, I had to call in reinforcements. I reached out earlier to the archivists and librarians at the United Nations Office in Geneva about my project, and they were able to provide students (and me) with two in-depth sessions introducing us into how to use the League’s online archival system. These sessions were invaluable in helping us turn general ideas for our videos into more specific, researchable tasks.

Teaching students across these three dimensions—the “what” of history alongside the “hows” of research in digital archives, scriptwriting, recording and producing—was never boring, to be sure. But it also highlighted how learning about history, “doing” history, and then translating our findings to popular audiences involves discrete skill sets. We quickly found how difficult it was to distill our research down to a 10- or 15-minute video, and we learned how wide the gap can be between written scholarly language and the short, punchy language that brings videos to life. Figuring out how we, as scholars comfortable in the written word, can productively interact with the attention economy of video remains a pressing task.

How do you grade a video?

This brings me to a second reflection on the course, namely how we grade and assess multimedia productions in the context of universities. Most university teachers have developed rubrics for how they grade final papers according to categories like organization, argumentation, and style. As I evaluated students’ final videos for “History Lab,” however, I struggled over how to weigh factors like the depth of their research in the League of Nations’ archives as opposed to the technical competence of the video itself.

Assessing the quality of students’ scripts was another challenge, since the more colloquial language that I tend to penalize in “normal” seminars was actually something to strive for in this new context. Determining how we grade students’ work in the video format remains an open question for me, particularly since self-presentation before a camera, much less scriptwriting and color grading, are seldom skills that students have trained at school before they arrive at the university.

In the end, I asked that students bring at least one primary source from the LONTAD collection into dialogue with secondary scholarship on the League of Nations. The point, as I saw it, was less for students to produce videos summarizing the tensions over disarmament or recapitulating the causes of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria – that’s what Wikipedia is for, and the scripts for such videos could easily be produced by AI. Instead, I asked students to show how they could bring new sources from the LONTAD collection to engage with scholarly debates: what, for instance, can petitions from minorities in Eastern Europe tell us about the League’s Minority Protection Treaties, or the limits of international protection for ethnic and religious minorities today? On the more technical side of things, I also expected students to show that they could use some of the techniques (whether inserting background images onto a green screen, or using effective transitions in DaVinci Resolve) that we had learned in special sessions at the ZHW or with external experts.

It’s particularly imperative for university teachers to have conversations about how to grade such multimedia assignments, not least as improving AI technology undermines the value of the traditional seminar paper as a measure of learning. As we continue to think about assessing student performance amid these challenges, we need to take care that our grading for such assignments reflects our learning goals, lest we merely reward students who arrive in the classroom with the best video production skills.

Conclusions

Would I do it all again and offer a similar course in the future that combined introduction to a historical topic with research skills and multimedia production? Absolutely! As these reflections show, however, perhaps the better question is whether it might not make more sense to break up “History Lab” into multiple individual seminars, each tailored to the learning goals I mentioned earlier. Digesting the entire history of the League of Nations or the international history of the interwar period is a tall enough order. Combined with a crash course in navigating 14.2 million digitized pages and a boot camp in film production, “History Lab” tested students’ ability to absorb information. Nonetheless, I can imagine turning these discrete skill sets into separate courses that might form a three-semester sequence and give students more time to turn the knowledge that they have acquired in one course into a professional quality script in another; then actually produce that script into a video in a third course.

In the meantime, moreover, I hope to think more about how we can develop rubrics for non-text based work and adapt our courses of studies and modules to reflect a changing scholarly ecosystem in which videos, podcasts, and other media occupy important space alongside written work. Here’s to further experiments and exchange about how we can integrate digital archives and multimedia work into history teaching at universities – and making sure that scholarly work in media like video is recognized as the contribution that it is.

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Nunan, T. (2024, December 12). From Archives to YouTube: Bridging Scholarly Research and Video Production. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20241212.EN

Timothy Nunan

Timothy Nunan is Professor for Transregional Cultures of Knowledge at the Department for Interdisciplinary and Multiscalar Area Studies at the University of Regensburg. His research focuses on international history, Russian and Soviet history, and the history of the modern Middle East. His first book,Humanitarian Invasion: Global Development in Cold War Afghanistan, examined the history of international development in Afghanistan during the Cold War. A forthcoming book project explores how the Cold War and decolonization transformed Shi’a Islamism during the twentieth century.