As lecturers, it’s an all too familiar scenario: endless piles of exams to mark, presentations that are often not as in-depth as we had hoped, and countless numbers of term papers at the end of the semester. I have been looking for ways to change this and to support and motivate students and take some of the stress of exams off them on a long-term basis. In this post, I present a concept that has meant that I have been able to lead heterogeneous groups to achieving real learning success and transform my teaching practice. The reference framework is the degree programme in education. One example that can be used to illustrate this is a seminar on the didactics of written language acquisition.

What are our stumbling blocks when it comes to assessments?

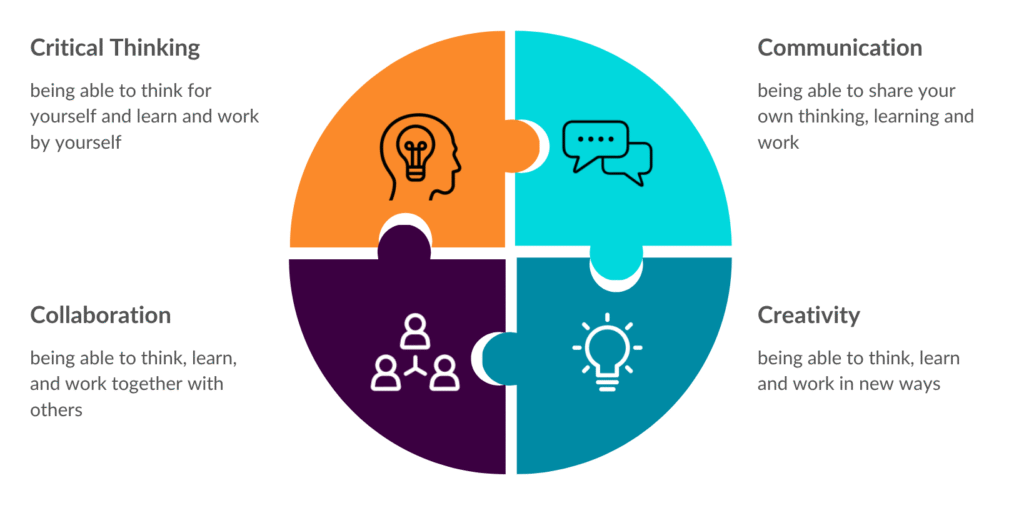

Due to digitisation, we all learn differently than we did a few years or decades ago (and that also includes our students). Meanwhile, other resources such as explanatory videos, ChatGPT and forums are also used now on top of the typical “cramming” of lecture notes. The expansion of learning opportunities is also accompanied by changes in skill requirements. The “4Cs” – communication, collaboration, creativity and critical thinking – are seen as the interdisciplinary core skills of the 21st century (Muuß-Merholz, 2017; Figure 1).

Assessments should also measure these skills according to the aspect of validity. However, conventional forms of assessment show their limitations here and can even be counterproductive: in traditional written exams, for instance, students have to write by hand and do the exams alone without exchanging or using resources (Krommer, 2021). This does not reflect the reality outside the lecture hall or seminar room – or when was the last time you did anything in your daily (professional) life in a way that was so isolated?

Furthermore, exams of this kind are often held in an “all-or-nothing” situation at the end of the semester during an exam phase that is stressful enough as it is. In the end, students are only given an abstract numerical grade after a while which gives little indication of further opportunities for development. This type of examination therefore fulfils a function that has to do with allocation alone – a kind of ranking. What is not considered to the same extent on the other hand is the qualification function, in the sense of elaborated feedback, opportunities for revision and consolidation, follow-up discussions and so on.

How can we overcome the stumbling blocks in assessments?

The options for overcoming stumbling blocks and for meeting the validity requirements outlined and the students’ needs can look very different depending on the teaching context and level of innovation.

I show you one of these below. It concerns a compulsory seminar on the didactics of written language acquisition, which is aimed at students in the 2nd to 5th semesters of degree programmes in special education and primary school teaching. What is notable here is that students typically have different levels of prior knowledge. In addition to overcoming the stumbling blocks mentioned above, my goal in this seminar is to practise interdisciplinary, teacher-specific skills as well.

The course was monitored and evaluated by the Centre for University and Academic Teaching (ZHW) at the University of Regensburg in the winter semester of 2024/25.

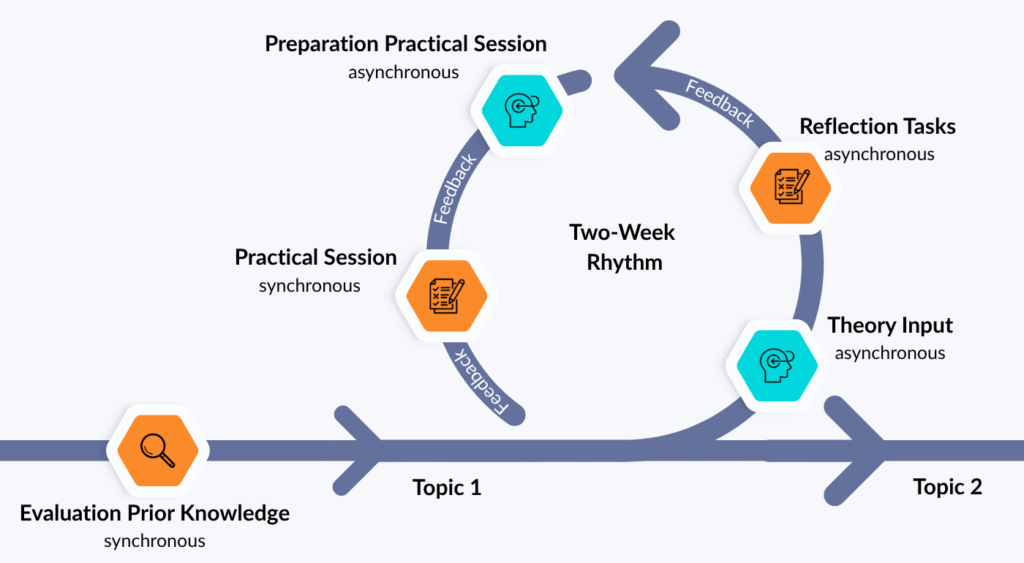

As you can see in Figure 2, I have basically designed the seminar so that one topic is dealt with over two weeks. I combine asynchronous and synchronous teaching/learning phases (Müller & Mildenberger, 2021) in a flipped classroom format (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2018), alternating on a weekly basis. In order to tailor the sessions to match the students’ starting points with regard to learning and to be able to recommend ways for them to work through the material, I assess their prior knowledge of all subject areas at the start of the semester (step 1).

On this basis, the students first work on the basic theoretical principles asynchronously in the one week (step 2). The asynchronous learning phases mean that students can arrange individually when to do their work and how quickly, and can apply their prior knowledge in a targeted and independent manner by delving more deeply into more exacting questions or by revising basic content as required. For this purpose, I provide them with specialist texts, research assignments and learning videos that I have created myself. Using central questions and small tasks, they reflect on, delve into and expand on what they have worked on, sometimes discussing it in forums or small groups (step 3). This forms part 1 of the assessment. By my assessing the students’ performance regularly, they receive constant feedback on their learning progress. Here, I find it particularly important to give elaborated feedback (Wisniewski et al., 2020): I mark each product submitted – be it a short video, a poster or a reflective essay – with specific pointers as to accuracy regarding subject matter and as to the further development of the student’s own ideas (step 4). This creates a continual dialogue between me as the lecturer and the students, in which strengths, gaps and improvement strategies are communicated clearly.

| Tip: The form of assignment is determined by how big your course is, how much personal support is required, what your students prefer and how much time you have: students can work on the tasks individually, in pairs or in groups and they receive feedback. |

In the other week, a specifically assigned small group in each case (with the option to choose) takes over the moderation of a synchronous face-to-face session. The aim of this session is for them to become acquainted with practical materials and methods and also with concepts and to evaluate them critically in the context of the theory addressed in the previous asynchronous session. In this sense, what is used instead of presentations involving the “talk and chalk” method is a learning setting that activates all the students: together with me as the seminar leader, the small group in each case plans a task to be performed using the station work method or similar interactive methods (step 5) and, as experts, guides their fellow students through various tasks concerning practical materials that build on the theory worked on during the asynchronous phases (step 6). This is part 2 of the performance assessment.

In this process, the principles of formative assessment are consistently applied and implemented: transparency, learning progression diagnostics, feedback, students taking responsibility for their own learning, and peer learning (Black & Wiliam, 2009).

What are the concrete benefits?

As the teaching analysis poll conducted by the ZHW has shown, the continuous work steps ensure that all the students remain constantly involved and do not merely get a certificate of attendance. By each student continually working on tasks, receiving constructive feedback and communicating with me as the teacher and with fellow students, a continuous learning process develops. As a result, students deal with the seminar content in depth and develop a deep understanding.

In addition, spreading assessments over the semester in this way reduces the exam load for students (and for us lecturers as well) during the general exam phase. As there is no “all-or-nothing” situation at the end of the semester, any difficulties with specific tasks can be compensated for by better results in other areas. The students are relieved of the pressure of there being only one examination day and it means that they can organise their own learning progress in a way that is more self-determined.

Furthermore, the opportunity to develop useful products during or for the synchronous practical sessions provides an experience of studying that is practical and motivating. Students can design support materials that are tailored to real-life teaching situations, for example. These products can serve as a resource during teacher training or at schools later. Organisational freedom also requires and fosters creativity – students can choose whether they would rather produce a poster, a video or a podcast, for example.

In my experience, their dealing with practical materials in depth has proven to be particularly beneficial for the learning process. It provides students with the opportunity to experience the complexity of the teaching profession early on. It means that preparation for the moderation phases leads not only to a deeper understanding of the content of the topics in each case but also to role training that is practically orientated: students act as instructors, answer questions on the subject and practise reacting spontaneously to unanticipated learning and discussion situations. By combining didactic skills, pedagogical skill and the direct assumption of responsibility in a didactic situation, this form of learning goes beyond the usual lecture formats. For prospective teachers in particular, this represents a valuable learning space that fosters both specialist and interdisciplinary skills and enables them to reflect on their own actions.

What does this mean in summary?

After implementing the concept I have presented, there is one thing I am sure of: in terms of formative assessment, exams are an integral and important part of the continual learning process and are far more than just performance assessments. What stands out regarding this concept is the fact that the students work continuously in asynchronous and synchronous phases on tasks that are practically orientated, receive ongoing elaborated feedback from me and take greater responsibility for their own learning. As the evaluation has shown, this dovetailing of teaching and examination is not only perceived positively by the students, but, in my experience, they also acquire ready-to-use specialist knowledge and key 21st-century skills – communication, collaboration, creativity and critical thinking.

What has your experience been?

How would you assess this concept for your own teaching context? What experience have you already had with similar approaches? Do you see any ways to incorporate formative assessment and flipped classroom elements into your courses? What opportunities and challenges would you expect to arise when implementing this in your heterogeneous student groups?

Let’s start a conversation, and feel free to share your thoughts on a channel of your choice: https://allmylinks.com/richard-boehme

References

Akçayır, G. & Akçayır, M. (2018). The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education, 126, 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.021

Black, P. & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

Krommer, A. (2021). Mediale Paradigmen, palliative Didaktik und die Kultur der Digitalität. In U. Hauck-Thum & J. Noller (Hrsg.), Was ist Digitalität? Philosophische und pädagogische Perspektiven (S. 57–72). Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-62989-5_5

Müller, C. & Mildenberger, T. (2021). Facilitating flexible learning by replacing classroom time with an online learning environment: A systematic review of blended learning in higher education. Educational Research Review, 34, 100394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100394

Muuß-Merholz, J. (2017, 21. August). Die 4K-Skills: Was meint Kreativität, kritisches Denken, Kollaboration, Kommunikation. Jöran & Konsorten. https://www.joeran.de/die-4k-skills-was-meint-kreativitaet-kritisches-denken-kollaboration-kommunikation/

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K. & Hattie, J. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Böhme, R. (2025, November 13). Dovetailing teaching and assessment: 21st-century skills meet student orientation. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20251113.EN

Richard Böhme

Prof. Dr. Richard Böhme has been a university professor for Sustainable Digitality at the Salzburg University of Education Stefan Zweig since October 2025.

Previously, he worked at the University of Regensburg in the field of primary education and didactics. His main interests are diagnosis and support in the area of literacy acquisition, digital technologies in educational contexts with particular consideration of AI applications, as well as inclusive approaches to diversity and education for sustainable development.

- This author does not have any more posts.