You’re a visual learner. We only use 10% of our brains. Best teaching is value neutral. Educational myths often appear in the form of phrases and platitudes. Although many of these questionable beliefs about educational phenomena lack empirical evidence, they tend to be widespread, persistent and have somehow managed to become everyday knowledge (De Bruyckere et al., 2020; Sinatra & Jacobson, 2019).

While these myths may blossom from a seed of a fact, they can be problematic, especially when lecturers unconsciously act on them, or even spread them. “One benefit of gaining a better understanding of how we reject other’s bullshit is that it may teach us to be more cognizant of our own bullshit” (Pennycook et al., 2015, p. 26).

The Challenge: Distinguishing Myth from Fact: What are Educational Myths?1

As in other domains, many myths and questionable assumptions exist in education. Educational myths are beliefs [about teaching and learning phenomena] that are held contrary to known evidence. They can be characterized as common and enduring beliefs, that might sound reasonable at first, but are not scientifically sound (e.g., Lilienfeld et al., 2010; Steins et al., 2021).

(Inter)national educational psychology research increasingly provides empirical evidence that certain educational myths are widespread despite the lack of empirical evidence – not only among lay people, but also (prospective) teachers and other professional educational staff (De Bruyckere et al., 2020; Lilienfeld et al., 2010).

Distinguishing myth from fact can at times be challenging as the controversial discussion and findings around Power-Posing show (e.g., Elsesser, 2020): The debate revolves around the idea that adopting expansive body postures can influence one’s feelings of power and behavior, a concept popularized by Amy Cuddy but later questioned due to inconsistent research findings, particularly regarding hormonal changes. Despite skepticism and intense academic scrutiny, which included personal attacks on Cuddy, meta-analyses have shown that posture does impact feelings of power, leading to continued research into its effects and applications (Gronau et al., 2017). All in all, power posing is between myth and fact, making a nuanced discussion necessary.

Causes and Sources of Educational Myths

The causes for the emergence of educational myths are manifold: educational myths often arise from logical fallacies and cognitive distortions: The overgeneralization of one’s own experiences or anecdotal evidence can contribute to the formation of myths. However, the simplified representations of teaching-learning phenomena in media articles, popular science guides and even scientific publications, as well as their misunderstanding or misinterpretation, can also lead to questionable beliefs (e.g., Lilienfeld et al. 2010).

The following interactive diagram displays some sources and causes of educational myths. It can help you to reflect on your personal experiences with educational myths.

Consequences of Educational Myths

The negative consequences of educational myths can be significant: They can lead to ineffective teaching methods (including discovery learning without scaffolding) that waste valuable time and resources. Moreover, misconceptions can also lead to false expectations and disappointment among teachers and learners. Furthermore, they can contribute to teachers and learners relying on inadequate or even harmful practices instead of using evidence-based approaches (e.g., Lilienfeld et al. 2010). The following interactive diagram sums up some negative consequences of educational myths for various stakeholders.

Challenges of Challenging Educational Myths

Previous research suggests that questionable beliefs about educational phenomena are generally stable, resistant to change and often deeply embedded in a developed knowledge structure (Sinatra & Jacobson, 2019). They are often upheld by tradition, social norms, or personal opinions. They are often presented in popular culture or the education system as universal truths or common sense. Some therefore speak of “zombie concepts” that “die hard” (Sinatra & Jacobson, 2019; Menz et al., 2021):

Remedies Against Educational Myths

Various authors have addressed common educational and psychological myths, taking different approaches:

6.1 Prevention Through Inoculation (“Protective Vaccination”):

This approach consists of making people aware of myths before they encounter them, thereby protecting them from adopting them. Through this preventive measure, people are better prepared and more resistant to myths (e.g., Lewandowsky et al. 2020, p. 6).

6.2 Identification with Heuristics:

With so many educational myths, it can be difficult to keep track of them all. However, there are characteristics that can be used to identify educational myths without having to know the details of each topic. Asberger et al. (2022) suggest using heuristics to identify and evaluate myths.

The concept of heuristics was introduced to the participants as simple, fast, and transparent decision-making strategies or “rules of thumb” (Gigerenzer, 2015) that they can use to identify educational myths (Asberger et al., 2022).The heuristics cheat sheet (Fig. 1) comprises eight heuristics such as the “Anecdotal-Alarm” or the “The One-Size-Fits-All Alert” (see e.g., Asberger et al., 2022). It can be used to identify potential educational myths by applying it to statements such as “discovery learning is a highly effective method for novice learners” (myth) and “handwriting notes isn’t necessarily superior to taking digital notes” (fact).The potentials (e.g., useful indicator for bullshit) and limitations of these heuristics (e.g., domain-specific content knowledge needed to make informed decision) should be kept in mind.

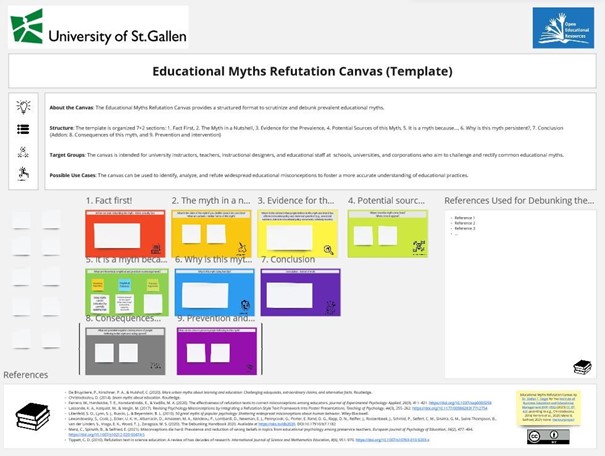

6.3 Intervention with Refutations (Debunking): Using the Educational Myths Refutation Canvas to Debunk Misconceptions About Teaching and Learning

Another approach is to specifically debunk myths by exposing and correcting the questionable assumptions. Other researchers have developed strategies to effectively debunk myths and help people build and use correct knowledge (e.g., Lewandowsky et al. 2020).

For this purpose, the newly developed Educational Myths Refutation Canvas (CC BY 4.0; Fig. 2) can be used to debunk questionable beliefs about teaching and learning. The following refutation template, a worked example (learning styles), and a refutations rubric for assessing the quality of your refutations can facilitate your debunking efforts:

The following interactive infographic summarizes the remedies against educational myths mentioned and contains continuous professional development and rigorous education research as additional counterstrategies:

Debunk Often and Effectively!

Dealing adequately with educational myths can be tricky as there are some potential pitfalls (e.g., focusing too much on facts; only debunking a myth without providing an alternative mental model). Nevertheless, I encourage you to debunk often and in a professional manner and fight sticky myths with sticky facts using the tools and knowledge provided in this blog post. As an (aspiring) educational myth buster make sure to use words people know, beware of motivated reasoning, and defense mechanisms.

A Closing Note

This blog post is based on a newly developed workshop that was successfully conducted within the further education program of the Centre of Learning and Teaching in Higher Education (HDZ) of the University of St. Gallen (HSG). This teaser video sums up the scope and approach of the workshop:

References

Asberger, J., Futterleib, H., Thomm, E., & Bauer, J. (2022). Wie erkennt man Bildungsmythen?: Sieben Heuristiken zum Selbsthinterfragen und Weitersagen. In G. Steins, B. Spinath, S. Dutke, M. Roth, & M. Limbourg (Eds.), Mythen, Fehlvorstellungen, Fehlkonzepte und Irrtümer in Schule und Unterricht (S. 3–26). Springer.

De Bruyckere, P., Kirschner, P. & & Hulshof, C. (2020). More Urban Myths About Learning and Education. Challenging Eduquacks, Extraordinary Claims, and Alternative Facts. Routledge.

Elsesser, K. (2020). The Debate On Power Posing Continues: Here’s Where We Stand. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kimelsesser/2020/10/02/the-debate-on-power-posing-continues-heres-where-we-stand/?sh=3d021ede202e

Gigerenzer, G. (2015). Simply rational: Decision making in the real world. Oxford University Press.

Gronau, Q. F., Van Erp, S., Heck, D. W., Cesario, J., Jonas, K. J., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2017). A Bayesian model-averaged meta-analysis of the power pose effect with informed and default priors: The case of felt power. Comprehensive Results in Social Psychology, 2(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743603.2017.1326760

Hawelka, B. (2022, 7. April). Mythen. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20220407.DE

Lewandowsky, S.; Cook, J.; Ecker U. et al., 2020. The Debunking Handbook 2020. https://sks.to/db2020. doi:10.17910/b7.1182

Lilienfeld, S. O., Lynn, S. J., Ruscio, J., & Beyerstein, B. L. (2010). 50 great myths of popular psychology: Shattering widespread misconceptions about human behavior. Wiley-Blackwell.

Menz, Cordelia, Birgit Spinath und Eva Seifried, 2021. Misconceptions die hard: Prevalence and reduction of wrong beliefs in topics from educational psychology among preservice teachers. In European Journal of Psychology of Education. 36(2), 477–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00474-5

Pennycook, G., Cheyne, J. A., Barr, N., Koehler, D. J., & Fugelsang, J. A. (2015). On the reception and detection of pseudo-profound bullshit. Judgment and Decision Making, 10, 549–563.

Siegel, S. T. (2023). Bildungsmythen. socialnet Lexikon. Bonn. https://www.socialnet.de/lexikon/29918

Sinatra, G. M., & Jacobson, N. (2019). Zombie Concepts in Education: Why They Won’t Die and Why You Cannot Kill Them. In P. Kendeou, D. H. Robinson, & M. T. McCrudden (Eds.), Misinformation and fake news in education (S. 7–27). Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Steins, G., Spinath, B., Dutke, S., Roth, M., & Limbourg, M. (Hrsg.). (2022). Mythen, Fehlvorstellungen, Fehlkonzepte und Irrtümer in Schule und Unterricht. Springer.

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Siegel, S. T. (2024, February 15). Myths Debunked. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20240215.EN

1This blog post is in parts based on Siegel (2023).

Stefan T. Siegel

Dr. Stefan T. Siegel is Postdoctoral Researcher and Lecturer at the Institute for Business Education (IWP) at the University of St. Gallen (HSG). He is the author of several (inter)national articles and books and has several years of work experience in research and teaching in (higher) education. He has been awarded several prizes for his work. His current work focuses on educational theory, professionalization of teachers, educational myths, and sustainability education.

- This author does not have any more posts.