Many lecturers wonder what motivates students to get their teeth into a topic – or not, as the case may be. Motivation is regarded as the essential key to academic success here. In practice, however, even highly motivated students often put off doing tasks, fail to achieve learning outcomes or sit on their hands despite their best intentions. The answer to this is provided by the psychological concept of volition. It is therefore worth taking a look at not only what we desire, but also what we actually do.

Desire: Someone who desires something is motivated and pursues a goal. People rate these goals according to opportunity, incentive and consequences (Puca & Schüler, 2024). Motivation is the driving force that gets students to grapple with learning content, for example, or encourages teachers to try out innovative teaching methods.

Action: Students learn – even if there are distractions, difficulties or inner resistance. This self-control is referred to as volition (Job & Goschke, 2024). Volition is what makes the difference between a well-intentioned study plan and consistent exam preparation.

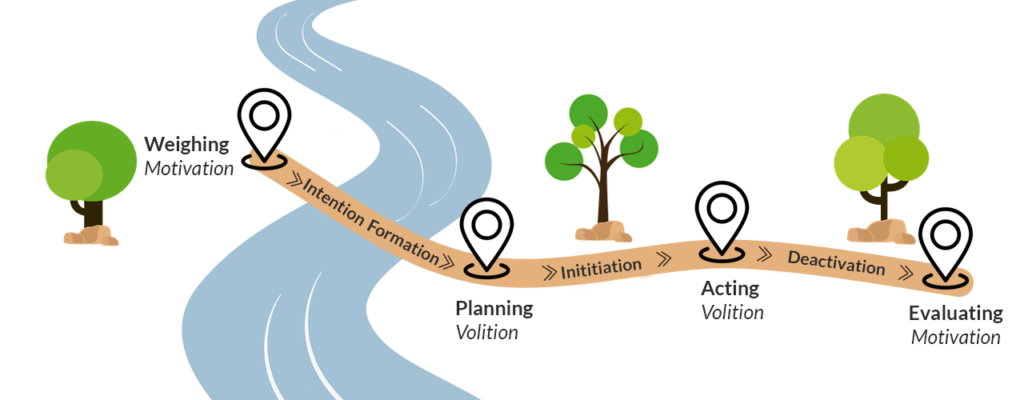

The established Rubicon model of action phases explains how the process from desire to action works.

The Rubicon model of action phases

Heckhausen and Gollwitzer’s Rubicon model of action phases (Heckhausen, 1987) refers to a historical event. In the year 49 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar and his troops crossed the small Rubicon river on the border between Italy and the Roman province of Gaul. This was forbidden and was considered a declaration of war on the Roman Senate. With his famous saying “Alea iacta est” (“The die is cast”), Caesar made it clear that there was no turning back. He had decided on an action that was irreversible.

Figuratively speaking, it means that people weigh up alternatives before crossing the Rubicon. After they have crossed the Rubicon, people pursue their chosen goals. In the model, the path from desire to the achievement of a goal is divided into four phases (Gollwitzer, 1996). Figure 1 shows the model in simplified form:

1. Weighing up phase: “What do I want?”

During this phase, people become aware of their wishes and goals. They assess how likely these are to be realised (expectation) and consider how important the goals are (value). This weighing up is accompanied by motivational processes, which lead to a decision being made. In the end, a goal is consciously selected, an intention is formed and the “Rubicon” is crossed.

Example: The four phases of the Rubicon model can be illustrated by the process of writing a Master’s dissertation. In the weighing up phase, a student considers whether or not she should start her Master’s dissertation and, if so, what topic she should do it on.

2. Planning phase: “How do I achieve my goal?”

This phase is volitional. In this phase, the focus is on self-control, with doubts or alternative options taking a back seat. The focus here is on goal alignment. The person plans the necessary resources, time and action strategies. Once a plan is in place, the intention is initiated. The action commences.

Example: The student has decided to start her Master’s dissertation. Once she has chosen a topic, she begins to plan the specifics. She thinks about a realistic time schedule, the breadth of the research question and the methodological skills required.

3. Action phase: “I’m doing it now!”

In this phase, the person puts her plans into action. She actively overcomes obstacles that jeopardise her achieving her goal. To do this, she needs the will to pursue her goal and self-control so that she does not get distracted or give up. The person shows discipline and perseverance (volition). After this phase is complete, the intention is then deactivated. Action ceases.

Example: The student begins to map out and write her Master’s dissertation. She tries not to procrastinate or get distracted or let any problems discourage her.

4. Evaluation phase: “Did I succeed?”

The person analyses whether she has achieved her goal or not and whether it was worth the effort. If she has succeeded, she considers the goal to have been achieved. If she has not been successful, the person can adjust the goal or give up. From the process evaluation she draws conclusions with regard to future decisions and plans. This has an effect on the motivation to tackle similar goals again. After submitting her Master’s dissertation, for example, the student asks herself questions about the development process:

What would she do differently next time?

What went well right from the start?

As soon as she is given the grade and feedback on her dissertation, she can continue this train of thought more rigorously and reflect on her approach.

The Rubicon model is typically presented as a linear process. This view is problematic as it usually ignores breaks in the course of action and overlaps between phases (Wiese, 2008). In practice, processes are dynamic:

There may be feedback loops or switching between the phases. During the planning phase, for example, the person might realise that the original goal was too complex or unrealistic. She might go back to the weighing up phase to reassess the goal. Or she might realise that her plan will not be adequate for her to achieve the desired goal.

In the above example, the writing of the Master’s dissertation will not be linear either. The student will have to keep adjusting her plan as she fleshes it out. She may notice errors in scheduling while she is writing the dissertation. Or she might realise that the topic is too broad and therefore needs to be narrowed down even further or even realigned. Hence, the model is not to be understood as a strict linear sequence of steps, but shows a dynamic process of motivational desire and volitional action (see Figure 2).

The Rubicon model gives lecturers concrete tips as to how they can support students in their learning process. Here, students are faced with several challenges.

They have to:

- research for information,

- choose a suitable goal,

- plan realistically,

- stay on the ball even when difficulties arise and

- draw the right conclusions in the end.

In order for students to manage these steps successfully, they require targeted offers that strengthen both their motivation and their volition.

Encourage volition – don’t just take it for granted

The following paragraphs contain suggestions as to how lecturers can support students in courses or when supervising dissertations. These suggestions are based on the phases of the Rubicon model.

Weighing up phase

At the start of a course or dissertation, lecturers should formulate and visualise the learning outcomes clearly. This means that students will be able to realise what to expect and what requirements they have to meet. Students have to be clear on what they have to accomplish. Transparency creates a sense of security: if you know what is required, you can choose your goal more consciously or complete a task successfully.

Lecturers can support the decision-making process by giving students feedback on their ideas and pointing out the advantages and disadvantages of different topics. Office hours provide space for students to present their own suggestions and, together with the lecturers, reflect on whether these are realistic and worthwhile.

Planning phase

As soon as students have established their goal or topic, they create a time schedule and work plan. Lecturers should review these plans and schedules and help the students formulate achievable interim goals. In order for the goals to be achieved, lecturers and students should work together to clarify relevant questions. What is particularly important here is to determine what is possible and what seems to make sense. Lecturers should also address potential confounding variables and how to deal with them. They should also refer to existing resources that facilitate the learning process. If students lack skills such as literature research or methodological knowledge, they can attend appropriate courses or be given targeted self-study units by the lecturers.

Action phase

Lecturers provide the impetus for action – by giving feedback or setting a clear time schedule, for instance. That way, they prevent students from getting stuck in endless planning without taking any action. If the students are active, regular progress meetings with constructive feedback are helpful. This enables them to assess their current level of performance adequately and receive support in time. Peer groups provide additional opportunities to discuss challenges and exchange ideas. Here, the threshold is usually lower than in conversations with lecturers. Small, regular tasks structure the work process and help keep the students working continuously. It is important for students to always be able to approach lecturers if problems arise.

Evaluation phase

Once a project or written assignment has been completed, it is evaluated. Lecturers should make it clear whether the goal has been achieved or not. Any gap between the actual situation and the target state should also be addressed. A final reflection phase helps students evaluate their learning process: what went well? What could be improved next time? This can be facilitated by lecturers inviting them to attend reflection and feedback sessions.

Conclusion

The Rubicon model shows that motivation is an important prerequisite for learning activities. However, it is actually volition that enables students to pursue their goals consistently and learn successfully during their studies. Therefore, students particularly benefit from higher education didactics that take both processes into account and foster them in a targeted manner. If you are interested in planning your course according to the Rubicon model, please write to us. We look forward to the conversation!

References

Heckhausen, H. (1987). Wünschen-Wählen-Wollen. In H. Heckhausen, P. M. Gollwitzer, & F. E. Weinert (Hrsg.), Jenseits des Rubikon: Der Wille in den Humanwissenschaften (S. 3–9). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-71763-5

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1996). Das Rubikonmodell der Handlungsphasen. In J. Kühl, & H. Heckhausen (Hrsg.), Enzyklopädie der Psychologie. Motivation, Volition und Handlung (S. 531–582). Hogrefe.

Job, V., & Goschke, T. (2024). Volition und Selbstkontrolle. In M. Rieger & J. Müsseler (Hrsg.), Allgemeine Psychologie (4. Aufl., S. 371–411). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-68476-4_10

Puca, R. M., & Schüler, J. (2024). Motivation. In. M. Rieger & J. Müsseler (Hrsg.), Allgemeine Psychologie (4. Aufl., S. 270–297). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-68476-4_8

Wiese, B. S. (2008). Selbstmanagement im Arbeits- und Berufsleben. Zeitschrift für Personalpsychologie, 7(4), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1026/1617-6391.7.4.153

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Puppe, L. & Rottmeier, S. (2025, October 16). The die is cast: The Rubicon model and its relevance for higher education. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20251016.EN

Linda Puppe

Dr. Linda Puppe is a research assistant at the Centre for University and Academic Teaching (ZHW) at the University of Regensburg. She focuses on the topics of innovation in teaching and motivation. Furthermore, she is interested in digital learning environments.

Stephanie Rottmeier

-

Stephanie Rottmeier

-

Stephanie Rottmeier

-

Stephanie Rottmeier

-

Stephanie Rottmeier