Even though fake news seems like a fairly recent phenomenon, it has actually been around far longer than social media or Donald Trump. In the realm of teaching and learning, half-truths and outright misinformation have been commonplace for much longer – and they’re here to stay. De Bruyckere, Kirschner & Hulshof (2015; 2020) have examined a number of these urban myths around teaching and learning in detail, three of which we will highlight in this post. All three of these myths are related to higher education, and they remain a fixture among both educators and learners.

Myths No. 1: The Learning Pyramid

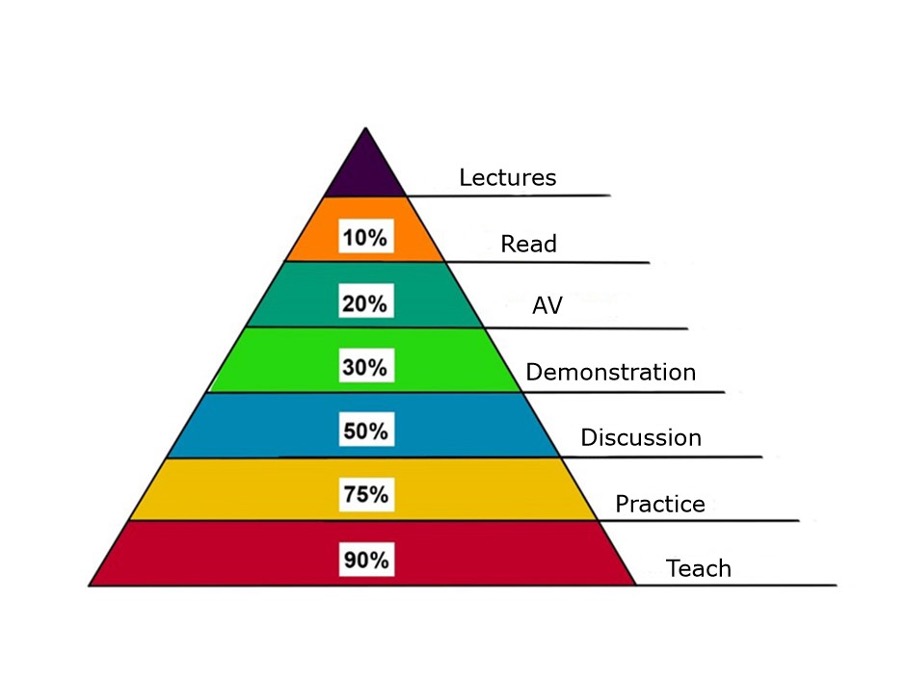

Learning pyramids rank different learning models according to their effectiveness. For instance, engaging in group discussion, reading, or practicing are ranked based on their respective degree of retention.

When trying to make a case for multimedia learning, people often refer to the learning pyramid, as it supports the idea that this approach is more effective than purely auditory methods. It’s also often cited as proof that active student participation leads to much better results than simply listening to a lecture.

As with so many urban myths, we cannot fully trace the origins of the learning pyramid. Perhaps the pyramid was first introduced in a book by John Adams (1910; cited in Bruyckere et al. 2015) entitled Exposition and Illustration in Teaching. Adams ranks each learning model by its level of effectiveness, suggesting that there is actual empirical support for their ranking. If we take the above pyramid at face value (Figure 1), we can conclude that for retention, watching a demonstration is three times more effective than reading. However, on closer inspection, we find that the numbers and the spacing in the pyramid are so evenly dispersed that we start to doubt that it is based on actual empirical proof.

More importantly, it would be very difficult to design studies using such wildly different variables. For one, the same instructor would have to teach the same topic to an identical group of students within the same time frame. Only the methodology would differ. Furthermore, each variable would need to be presented with the same level of quality in terms of teaching methods (however this is defined).

So far, despite concerted efforts, no such study has been found.

Myths No. 2: Types of Learners

We all learn differently. While some people are visual learners, others thrive when they are left to their own devices and allowed to engage in self-directed learning. Educators should adapt their methods to suit the needs of all types of learners and give them access to educational material that matches their individual learning styles.

While this may seem like a fairly intuitive assumption to make, there is no real evidence to support it. Various theories and tests (e.g. Kolb & Kolb, 2013; Vester, 2007) have attempted to categorise students into different types of learners, yet these categories are problematic on a number of different levels:

- It’s not a black and white issue. No student can neatly fit into any one category.

- Still, educators often overlook this basic fact, and so they reach the following conclusion based on a student’s personal preference for a specific method of learning: Learner A is a visual learner, which means that their learning is best supported when presented with visual content and material. Another example: Learner B is a reflective learner, so the best way to support their learning is by providing them an opportunity to reflect on specific experiences.

De Bruyckere et al. (2015) present a compelling case for comparing the alignment of teaching methods with learner needs and dietary practices. Many people have a preference for a certain type of food or flavor profile. Some have a sweet tooth, others prefer savory foods. However, just because someone can’t resist candy doesn’t mean their diet is healthy. On the contrary: We know that a poor diet can result in serious illness and disease, such as diabetes and obesity.

Learner types are no different. People simply have different preferences when it comes to absorbing knowledge and information, hence the proliferation of different teaching methods to accommodate these preferences. However, as far back as forty years ago, Clarke (1982, cited by de Bruyckere et al., 2015) points out that the use of preferred forms of teaching does not produce better learning outcomes. In fact, the approach has little or no effect on students’ learning. Instead, it is the intended learning outcome that determines whether a particular teaching method is effective. If the goal is to get students to critically engage with hypotheses they are presented with, engaging in group discussion is certainly an efficient approach. On the other hand, visual aids can help students build mental models. Unfortunately, though, there is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to learning.

Myths No. 3: Speed Reading

From time to time, we get requests for workshops and seminars on speed reading. It only makes sense – after all, a glowing endorsement from us would make the lives of countless lecturers much easier. We know that in the context of higher education and teaching, it’s not just essential to read as much as possible as quickly as possible, it’s just as important to understand what you’re reading.

De Bruyckere et al. (2020) set out to examine whether speed reading is the solution to this particular predicament. Their very simple answer to all impatient readers out there is: NO. That is exactly why we don’t offer workshops or seminars that involve speed reading in any way.

However, if you’re curious and want to learn more, feel free to consult Rayner et al.’s study (2016) where they debunk the speed-reading myth, once and for all. They review studies on different speed-reading techniques, such as optimizing eye movement, improving peripheral vision, or suppressing inner voices while reading. The conclusion they reach is damning for fans of speed reading – none of the above methods work without also diluting the reader’s text comprehension. In a sense, then, reading is about finding a balance between accuracy and speed.

Still, skimming texts can be a very useful skill for learners. By skimming the headline, paragraph structure, or looking for key terms, readers can quickly get an overview of the text’s central themes, thus increasing their cognitive space to engage with it. Following the first reading, a second, more detailed read then allows readers to extract and organize important information. The result is a more efficient approach to reading, but it is certainly no less time-consuming. Skimming texts will only ever benefit readers if they notice that a second read is not going to be rewarding for them as they are skimming it for the first time.

Of course, there are a lot more myths and assumptions related to teaching and learning besides the three we highlighted in this post. If any come to mind, feel free to let us know in the comments. We’ll be sure to debunk them in a future post.

References

De Bruyckere, P., Kirschner, P. & & Hulshof, C. (2015). Urban Myths About Learning and Education. Academic Press.

De Bruyckere, P., Kirschner, P. & & Hulshof, C. (2020). More Urban Myths About Learning and Education. Challenging Eduquacks, Extraordinary Claims, and Alternative Facts. Routledge.

Kolb, A. & Kolb, D. (2013). The Kolb Learning Style Inventory – Version 4.0. A Comprehensive Guide to the Theory, Psychometrics, Research on Validity and Educational Application. https://learningfromexperience.com/research-library/the-kolb-learning-style-inventory-4-0/

Rayner, K., Schotter, E., Masson, M., Potter, M & Treiman, R. (2016). So Much to Read, So Little Time: How Do We Read, and Can Speed Reading Help?, Psychological Science in the Public Interest 17(1). DOI: 10.1177/1529100615623267

Vester, F. (1998). Denken, Lernen, Vergessen. dtv

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Hawelka, B. (2022, April 7). Myths. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20220407.EN