When formulating intended learning outcomes, many people think of Bloom’s taxonomy or language exercises that tend to be quite boring. This blog post shows that intended learning outcomes in the academic arena involve much more than knowledge alone and how you can formulate intended learning outcomes quite quickly and easily with the help of a few little tricks.

Intended learning outcomes describe the knowledge and skills students should have by the end of a degree course or course of lectures and seminars. Or in other words: objectives – also called intended learning outcomes – specify the competencies students should have attained by the end of the learning process. These competencies are shown by how well students are able to solve particular problems (Weinert, 2001).

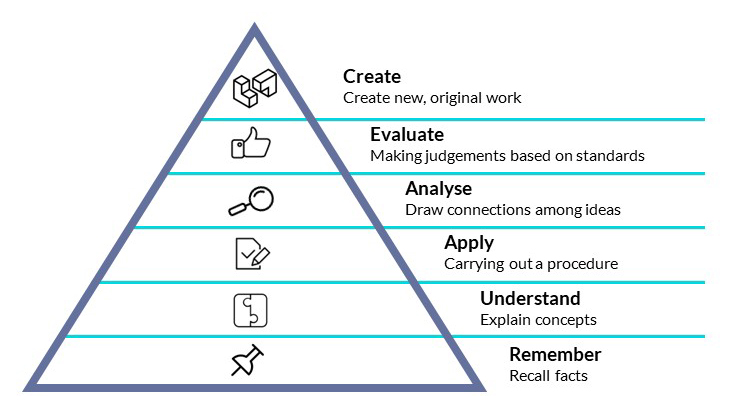

In the academic arena, problem-solving requires a wide range of competencies. These range from the simple summary of theories all the way to innovative and interdisciplinary problem-solving based on findings (Schaper, 2012). In order to illustrate different degrees of difficulty and complexity, the intended competencies are classified hierarchically in taxonomies. The higher the level, the more challenging the tasks that can be mastered on that level.

Taxonomies categorise intended learning outcomes by complexity

Taxonomies of intended learning outcomes are closely associated with the name Benjamin S. Bloom. In actual fact, he was the first to develop taxonomies of intended learning outcomes together with colleagues (Bloom et al., 1956). His original idea here was very pragmatic in nature: Bloom wanted to compile a database of different test questions to make the exchange between universities easier and thus reduce the time and effort required when preparing for the annual exams (Krathwohl, 2002). This database was to contain questions that were different but which all involved an equivalent degree of difficulty. Together with a group of experts, Bloom collected exam questions for several years and categorised them in taxonomies based on their underlying complexity. Later, members of Bloom’s team (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001; Krathwohl, 2002) revised the taxonomies he had drafted and then added extra aspects.

The most common and well known is the taxonomy of cognitive intended learning outcomes (Krathwohl, 2002). This includes these six categories: (1) remember – (2) understand – (3) apply – (4) analyse – (5) evaluate – (6) create.

Each category describes a competency at a certain competency level, with the individual levels building on each other: mastery of each simpler category (e.g. remember) is the prerequisite for mastery of the next category up in complexity (e.g. understand).

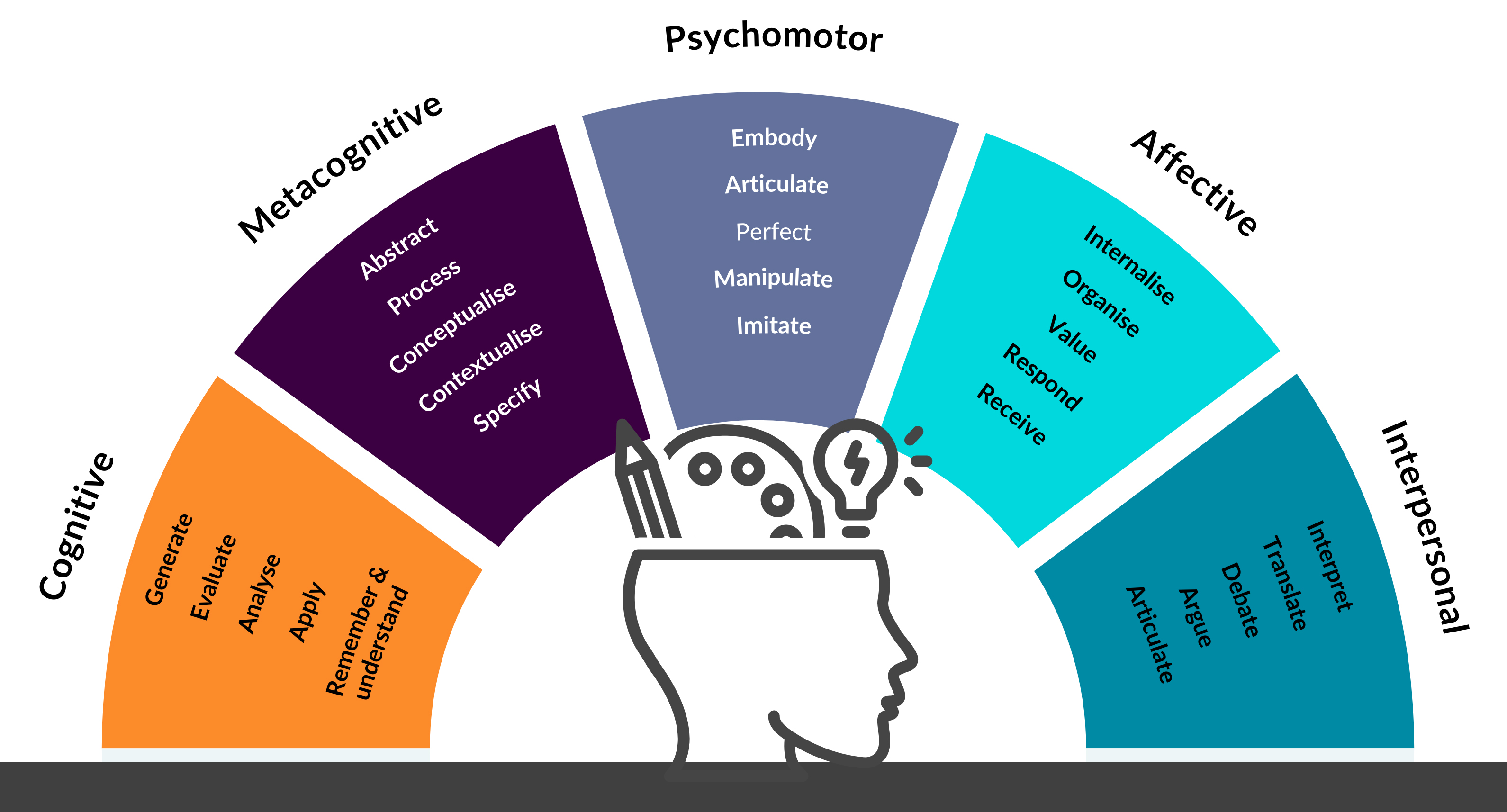

Intended learning outcomes include different competency domains

Even if the emphasis often lies on the acquisition of cognitive competencies in the academic environment, when it comes to mastering complex problems they are seldom sufficient on their own. In fact, budding academics are expected to be able to control and reflect on actions independently when solving problems. To do this, metacognitive competencies are essential. Many academic domains also require manual or physical skills (such as examination techniques, the operation of equipment or the mastery of particular sequences of movement). Furthermore, complex tasks are generally completed in teams rather than by one individual person. Cooperation can only be successful if all members have extensive interpersonal competencies in communication, conflict resolution and cooperation. A further aspect of academic competency goes beyond the mere solving of problems: students are the budding decision-makers of tomorrow. Building affective competencies in terms of a discerning value system is therefore an essential part of any academic training.

In an overview, Atkinson (2022) collected, modified and sometimes added to common taxonomies of intended learning outcomes. Figure 2 provides an overview summarising the individual competency domains and the respective levels.

Intended learning outcomes describe activities

What the taxonomies of all competency domains have in common is that at every competency level they describe activities that can be used to identify a specific competency. As the competency level increases, these activities become more complex and challenging. It makes a big difference, for instance, whether or not students

● can define the term “learning motivation” or

● can describe important factors related to people or situations that influence learning motivation or

● can explain how the basic needs according to Deci and Ryan influence learning motivation or

● are able to develop a concept for how they can specifically encourage pupils’ learning motivation in class as teachers.

Therefore, on a language level, intended learning outcomes always consist of at least two parts: (1) a verb or verb phrase describing what students can do and (2) a noun or noun group – the subject content (Krathwohl, 2002).

For clarification, the verb phrases in the following examples are marked in blue and the nouns in orange:

By the end of the module, students are able to

… generate suggestions for solutions to complex energy management problems.

… modify guidlines for the improved quality control of production processes.

… classify reactions as exothermic und endothermic.

.… list criteria that should be taken into account in the treatment of tuberculosis patients.

Intended learning outcomes in practice

There are various lists of verbs that are helpful tools fordescribing competencies at different levels, with the list of verbs according to Atkinson (2022) being particularly comprehensive, containing numerous verbs for all the competency domains presented in Figure 2.

In practice, the following approaches have proved their worth when it comes to formulating intended learning outcomes:

(1) Intended learning outcomes are formulated and described from the students’ point of view with regard to what students will be able to do after a learning unit (a lecture or seminar, a module or the degree course) has been completed. Therefore, intended learning outcomes begin with a sentence like “After the students have successfully completed this module, they will be able to …”.

(2) Intended learning outcomes also need to be verifiable. Therefore, avoid vague target formulations like “understand” or “have an overview”. How would you be able to discern whether your students had understood something? Or that they had an overview of a particular subject area?

(3) Remember that competencies do not only include cognitive outcomes, so formulate outcomes from other competency domains as well (see Figure 2).

(4) Intended learning outcomes are rarely final or all-embracing. Instead, they describe the minimum standard acceptable for students to be able to pass a learning unit.

(5) Intended learning outcomes must be realistic, i.e. it must be possible to achieve them with the resources available and in the time available.

(6) Intended learning outcomes focus on the most important competencies to be acquired. That is why it makes more sense to list a small number of relevant learning outcomes rather than a large number of superficial ones.

(7) The intended learning outcomes also need to become more complex the further on the students are in their studies. At Master’s level, intended learning outcomes are ranked more highly in the taxonomy than those at Bachelor’s level.

Intended learning outcomes that are precisely defined make the teaching-learning process easier for lecturers and students.

From the students’ perspective, clearly defined intended learning outcomes increase the transparency and logic of the learning process. By the learning outcomes pursued showing the students what skills a learning process (i.e. a lecture or seminar, a module or a degree course) will give them, they have a motivating effect. At the same time, intended learning outcomes guide the learning process and enable the students to reflect independently on whether they have already achieved the objective of a lecture, seminar or module or not, and to what extent. The blog post on the topic Three Reasons Why Articulating Course Objectives Is Vital shows how this can be put into practice.

From the lecturers’ standpoint, learning outcomes make it easier to coordinate teaching and exams coherently. How this can work will be explained in more detail in one of the coming posts.

References

Anderson, L. W. & Krathwohl, D. R., et al. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Atkinson, S.P. (2022). Writing Good Learning Outcomes and Objectives. Sijen Education.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. David McKay.

Green, G. (2023, January 4). The Terrible Tedium of ‘Learning Outcomes’. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-terrible-tedium-of-learning-outcomes

Krathwohl, D. (2002). A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212 – 218.

Schaper, N. (2012). Fachgutachten zur Kompetenzorientierung in Studium und Lehre. HRK Nexus. https://www.hrk-nexus.de/fileadmin/redaktion/hrk-nexus/07-Downloads/07-02-Publikationen/fachgutachten_kompetenzorientierung.pdf

Weinert, F. E. (2001). Vergleichende Leistungsmessung in Schulen – eine umstrittene Selbstverständlichkeit. In F. E. Weinert (Hrsg.), Leistungsmessung in Schulen (2. Aufl., S. 17-31). Beltz.

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Hawelka, B. (2024, August 15). From knowledge to expertise: Formulating intended learning outcomes. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20240815.EN

Birgit Hawelka

Dr. Birgit Hawelka is a research associate at the center for University and Academic Teaching at the University of Regensburg. Her research and teaching focuses on the topics of teaching quality and evaluation. She is also curious about all developments and findings in the field of university teaching.