During the COVID pandemic, the majority of the teaching was represented using media, with asynchronous videos particularly being used alongside video conferences (e.g. via Zoom). A recent meta-analysis in the Review of Educational Research verifies that the use of video can be more than just a stopgap.

It is not just since the COVID pandemic that video has played an important role in teaching. The formats used range from educational films produced with a great deal of time and effort to brief explanatory videos to PowerPoint slides set to music. What all formats have in common is that they combine moving images with sound. In contrast to video conferences, the content is produced beforehand, recorded and presented asynchronously. It is therefore not possible for lecturers and students to interact directly and dynamically.

There are many reasons in favour of using video

Video is firmly anchored in higher education – if only for pragmatic reasons. It enables students to learn independently of specific times or locations – on open university courses, for example, or when contact to others is restricted. But they are also used in in-person settings where the lecturer wants to show content that cannot be presented in real life or where its presentation would involve a great deal of time and effort. This is the case, for instance, if the object being shown is very small or very large, if processes that are very fast or very slow in reality are supposed to be simulated, or where the application of cases needs to be realistic and situated (in medicine, for example).

Findings from media education suggest that video can also support students in their learning process due to these purely practical advantages. The fact that the targeted combination of text and image can increase retention performance is well documented (Mayer, 2012). Other studies (Schneider et al. 2018, for example) show that the learners’ cognitive load is reduced by the possibility of repeating, skipping and pausing content whenever they like.

Meta-analysis with sophisticated study design

In a large-scale meta-analysis, Noetel et al. (2021) studied the effects that the use of video has in university teaching specifically. From what were initially 329 studies on the subject, the authors selected 105 for closer analysis. These included studies where

- the study design was randomised,

- video was determined an independent variable,

- video was the only essential change in the study design (studies on flipped classrooms, for example, were therefore excluded, as, in addition to videos, students were offered a learning experience that was substantially different),

- the participants were exclusively from universities, and

- the learning success was measured using tests or exams (therefore not self-reported learning success or subjective satisfaction).

Most of the studies selected (n=84) study the effect of video if it replaces existing learning formats, while 34 others study the effect if learning formats are supplemented by video. Twelve of the studies mentioned above address both questions. Noetel et al. (2021) calculated the pooled effect size (g) from the studies included. This reveals how strong or weak the effect is when video is used in comparison to a conventional learning environment (control group).

Different moderating variables were also taken into account here, particularly

- the learning environment (e.g. use in lectures, tutorials or independent study),

- the comparison conditions (is the video replacing a lecturer or static media?),

- the learning outcomes (knowledge or skills) and time of examination (immediately after learning or with a delay),

- the relative duration of the intervention (was the duration longer or shorter than for the control group or comparable with it?) and the absolute duration,

- the interactivity of the learning environment (compared to the control group),

- and frame conditions with regard to the field of study, the region and the funding of the measure.

Video can replace other forms of learning

All in all, it was revealed that various forms of learning can indeed be replaced by video. Here, the calculated effect of video is moderate overall (g = 0.28) compared to other forms of learning. The results of the individual studies vary greatly, however: video showed a good effect (g >.20) in half of the learning settings studied. In roughly one in three studies (31%) the effect was negligible, and 19% of the studies even showed a negative effect.

It is therefore worth taking a look at the specific conditions in which each video was used.

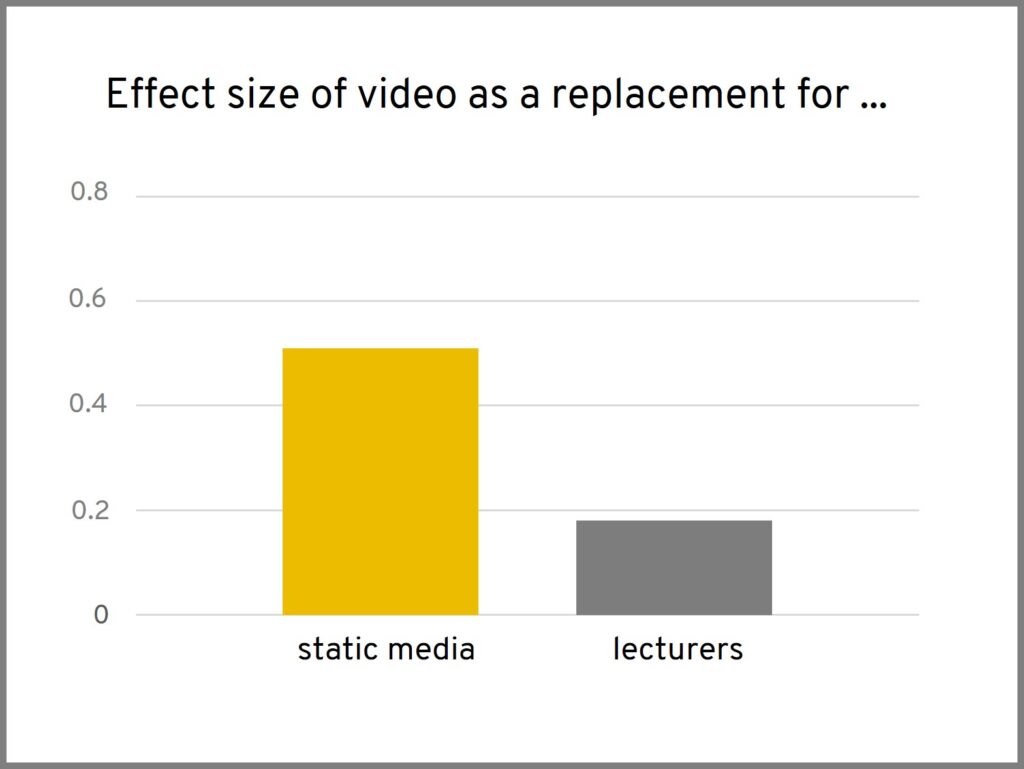

Video shows a moderate advantage (g = 0.51) over static media like books, for example. It only achieves a weak effect (g = 0.18) if it is used to replace a lecturer (see Figure 1).

These results confirm the hypotheses of the cognitive theory of multimedia learning (Mayer, 2008). Whilst text, for example, only caters to the taking in of information visually, the learning content can be taken in and processed better when there is a targeted combination of visual and aural information. This generally has a positive impact on the learning effect. At the same time, with videos students can determine their learning pace themselves – which is not the case with lectures and seminars that they attend in person. They can repeat sections as often as they like and decide themselves when to take breaks from learning and for how long. It is conceivable that lecturers pay closer attention to structuring the learning media in an appealing and coherent way when they produce videos than they would in a live situation. The production of educational videos means that sections can be cut out or added later. Essential points can be highlighted and charts superimposed so that they match the text of the lecture perfectly. That way, lectures can be optimised didactically with a very little time and technical outlay being required.

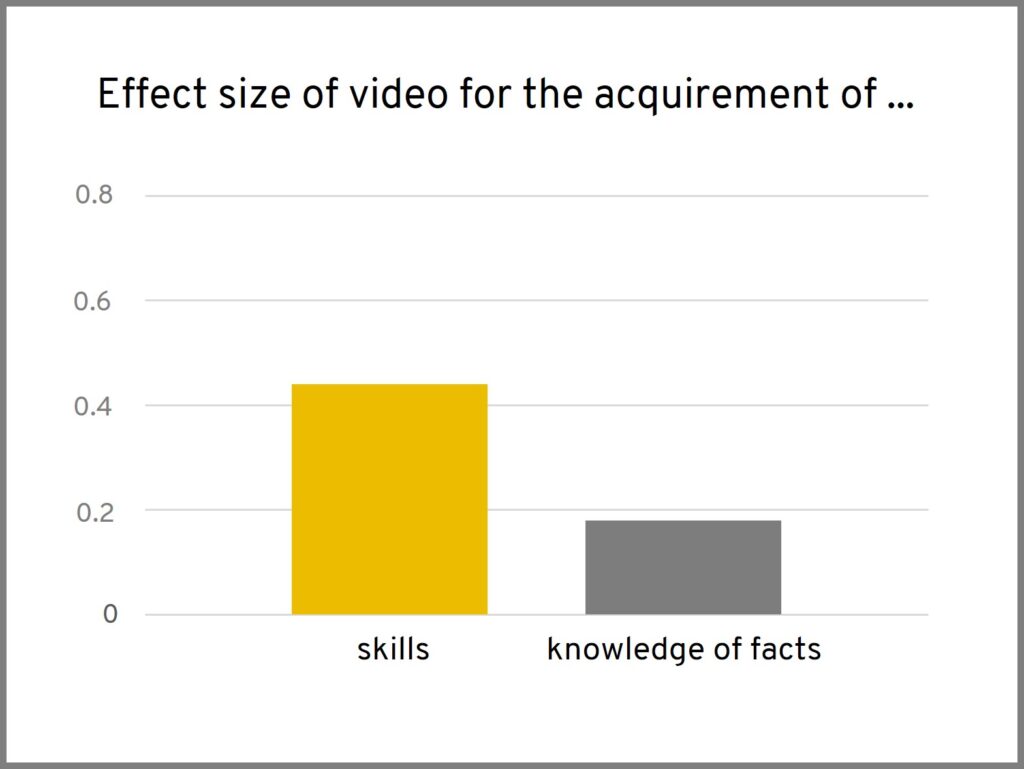

Whether or not the use of video pays off also depends on the intended learning outcomes. Video obtains good effect sizes where it pursues the acquirement of skills as a learning outcome (g = 0.44); when it comes to the acquirement of knowledge of facts, on the other hand, it has a smaller advantage (g = 0.18).

This can be explained by the fact that videos are able to show authentic and realistic problems and solutions to them. Knowledge of facts alone can be represented well verbally and illustrated well with charts if necessary. Skills such as surgical techniques in medicine or options for empathic conversation techniques in psychology, however, can be processed more visually in videos.

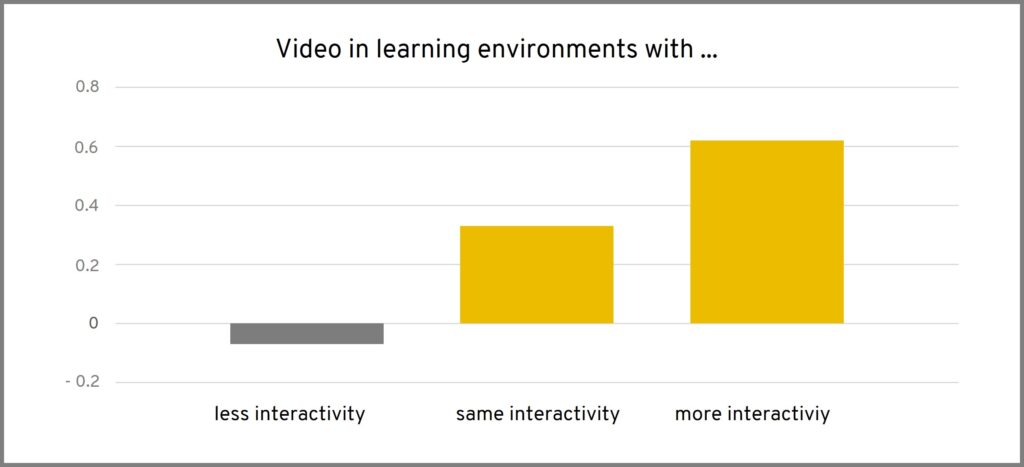

The degree of interactivity of the learning environment in which the videos are presented proved particularly significant. When videos were presented in learning environments that were less interactive than in the control group, the use of video did not show any advantage (g = −0.07). However, even where the level of interactivity was the same, the videos proved to be more effective (g = 0.33). Particularly large effects were measured when video was combined with a greater possibility for interaction (e.g. by students watching together) (g = 0.62). Figure 3 shows the effect of video in learning environments where the interactive structure was weaker or stronger than that of the control group or was on the same level.

This is further evidence to show that the possibility of actively preparing content knowledge in an interactive learning environment is one of the most significant factors when it comes to effective learning.

None of the other control variables studied had any impact on the effect of video in learning settings.

Videos should complement other forms of learning.

In their analysis, Noetel et al. (2021) also looked into the question of how effective video is when it complements other forms of learning. Regarding this aspect, the answer can be found considerably more quickly and easily. The overriding majority of the studies (88%) showed a strong effect when video was used as a supplement. Video only achieved a negative effect on the learning success in 2% of the studies.

Overall, an effect size of g = 0.80 speaks very clearly in favour of using video to complement other forms of learning and learning media in higher education. With only one exception, none of the variables studied had a significant impact on the effect size. What is surprising at first glance is that the type of funding of the respective projects influenced the effectiveness of video. Studies funded by external sponsors show a greater effect than those with no additional funding. The authors explain this effect by suggesting that the design of videos with third-party funding may have been more sophisticated and greater attention may have been paid to implementing findings from media didactics.

The use of high-quality video can enhance in-person teaching

So what can we take from this large-scale study? First of all: video is a medium that is very suitable for preparing learning content at university. It is therefore worth investing time and energy in producing well-thought-out educational films. Arguments claiming that it would be no problem to replace the majority of teaching with video-based formats in the future are not supported by the analysis, however. Instead, what it reveals is that great effects are particularly obtained when video supplements in-person teaching. It is actually the interactivity of in-person teaching with social exchange about the content of the videos that make them a valuable supplement to the methodological repertoire in higher education.

Therefore, the production of high-quality educational videos is not only a solution for emergency remote teaching but an investment in order to create in-person teaching that is even more effective in future.

References

Mayer, R.E. (2012). Multimedia Learning (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press DOI: 9780511811678

Noetel, M., Griffith, S., Delaney, O., Sanders, T., Parker, Ph, del Pozo Cruz, B. & Lonsdale, Ch. (2021). Video Improves Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. Review of Education Research, 91 (2). DOI:10.3102/0034654321990713

Schneider, S., Nebel, S., Beege, M., Rey, G. D. (2018). The autonomy-enhancing effects of choice on cognitive load, motivation and learning with digital media. Learning and Instruction, 58, 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.06.006

Suggestion for citation of this blog post

Hawelka, B. (2021, May 6). Video in higher education: More than emergency remote teaching. Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg. https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20210506.EN

Birgit Hawelka

Dr. Birgit Hawelka is a research associate at the center for University and Academic Teaching at the University of Regensburg. Her research and teaching focuses on the topics of teaching quality and evaluation. She is also curious about all developments and findings in the field of university teaching.